Today’s post comes from Rachel Wimpee, Historian and Project Director in our Research and Education division. Rachel uncovered this story while working with the Ford Foundation archives held at the RAC, and asked if it might be worth posting here. I only had to quickly skim the text to see the relevance for this blog.

A couple of broad themes jumped out at me when I read this piece. The first is the durability of modes of speaking and thinking about technology, which seem to persist despite (or perhaps because of) rapid technological changes. Artificial intelligence and machine learning, both hot tech trends currently, figure heavily in this story from 1965. You’ll also notice efficiency being employed as the ultimate justification for technology, even in a situation where increasing the profit margin didn’t apply. This story is also an excellent illustration of the socially constructed nature of technology. As Rachel’s piece reveals, technology is the result of consensus and compromise. There are negotiations mediated by money, practicality, and personality. Not only that, but technology and underlying processes are often so intertwined as to be indistinguishable, and each is often blamed for things the other produces.

In many ways, this is cautionary tale of what happens when we start with the new shiny thing rather than the needs of users (something that Evgeny Morozov and others have called “solutionism”). It’s not all bad, though. Rachel writes about the training plan implemented by the Ford Foundation at the same time staff began to use an IBM 360/30 mainframe for data processing in the late 1960s, as well as a regular process of evaluation and change implementation which lasted well into the 1970s. This reminded me of the importance of ongoing cycles of training and evaluation. New technologies usually require humans to learn new things, so a plan for both teaching and evaluating the effectiveness of that teaching should be part of any responsible technology change process. The D-Team is thinking a lot about training these days, particularly in the context of Project Electron, which will embed technologies into our workflows in holistic way. Even though the project won’t be complete until the end of the year, we’re already scheduling training to amplify our colleague’s existing skills and expertise so they can feel confident working with digital records.

In early spring 1965, the Ford Foundation’s Vice President for Administration and Operations, Verne Atwater, asked his team to investigate how a new technology called “electronic data processing” might be put to use at the Foundation. The task reflected the widespread mid-century faith in technology’s capacity to improve bureaucratic efficiency and enable management decisions to pack a bigger punch. Mechanized processing seemed to promise to make human decision-making foolproof by calculating risks and objectives as if they were purely mathematical. In short, Ford’s work might benefit from the budding field of artificial intelligence.

Julius Stratton, elected Foundation board chair in 1965, had been a Ford Trustee for ten years. He was also the chancellor of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The decade of Stratton’s trusteeship, 1955-1965, also witnessed the birth of a “new field of mathematical models for thought” (source). While Ford was not a major philanthropic funder in that field (the Rockefeller Foundation had been since the 1930s), in their professional lives, Stratton and other Ford leaders were deeply involved in the emergence and adoption of computer technology and artificial intelligence: Ford president H. Rowan Gaither (1953-1956) was one of the founders of the RAND Corporation, a think tank providing research and analysis to American armed forces. Ford president Henry Heald (1956-1966) was one of the founders of the Illinois Institute of Technology. Ford Trustee Bethuel Webster was on the board of the Systems Development Corporation, considered to be the world’s first software company. By 1965, when Atwater began investigating computer opportunities at the Ford Foundation, MIT’s “Project MAC” was developing artificial intelligence systems with U.S. Defense Department funding. Just a few months later, U.S. National Security Adviser McGeorge Bundy would assume the presidency of the Ford Foundation.

It was finally time for Ford to get a computer.

One astute Ford colleague, Deputy Director of Administration Richard S. Reed, was keen to point out that any technology was only as effective as the human-designed system it would replace. “Before we allow ourselves to get completely enamored of mechanization or computerization, we should realize that the only thing a computer will do for a poor system is to produce the same poor results at a much faster rate.” (Reed memo to Atwater, March 23, 1965. RAC) Reed titled another 1965 memo “Data Processing for What?”

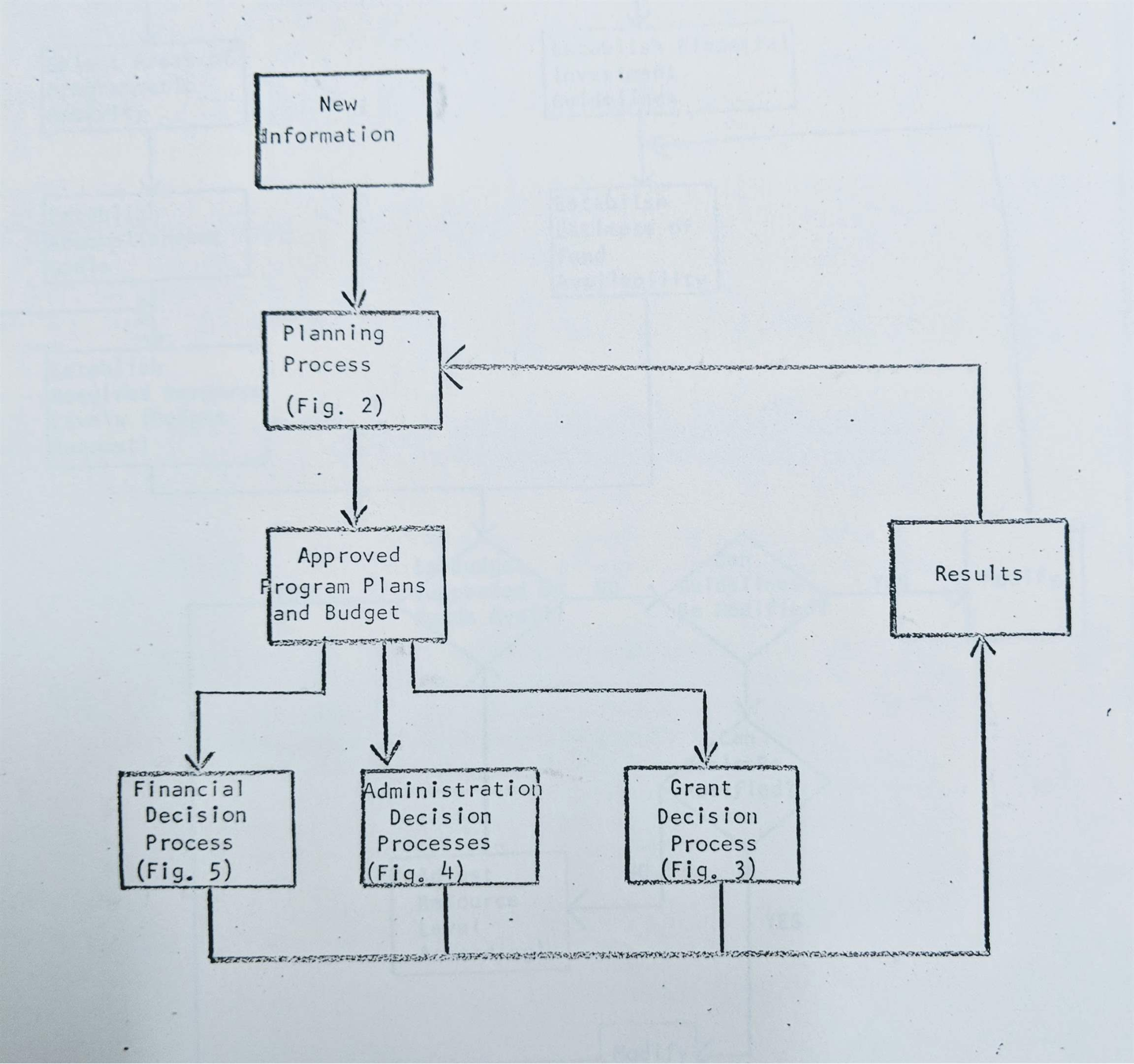

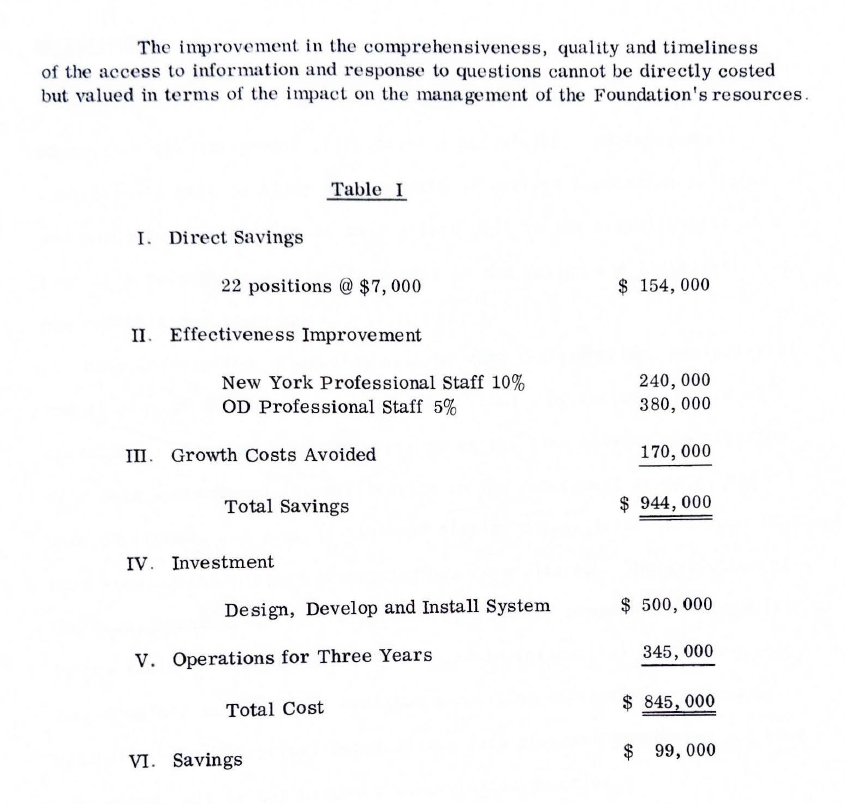

The Foundation hired Documentation, Incorporated, a computer and systems consulting firm, to examine its operations over twelve weeks in the spring of 1966. Approaching the Ford Foundation much as it would a corporate entity, the company’s feasibility study report made an economic argument for a Foundation-wide management information system of the most sophisticated type available. They proposed a system based on machine learning, which could change its parameters as it received new inputs. The system was estimated to cost $845,000 over three years (or approximately $5.5 million in 2018 dollars). Even for the billion-dollar Ford Foundation, this was an astronomical operational cost.

Documentation, Incorporated proposed raising the necessary funds through the elimination of twenty-two staff positions (clerks, typists, assistants), resulting in an annual savings of $154,000—not nearly enough. The study authors then suggested that the new system would so increase the efficiency of existing program professionals that it would essentially result in a savings worth $620,000. Adding to that an elimination of growth costs would result in net savings of $99,000, so the reasoning went. This argument might be persuasive for companies making products for profit. But everyone failed to notice that increasing the “efficiency” of Ford Foundation program staff— whose job was giving money away— would not result in cold, hard cash.

The new system’s price tag might nevertheless have been worth it if it could have helped Ford staff make more informed decisions, rule out less-promising programmatic options, and calculate safe doses of risk. But upon further examination, it was clear that even the manual administrative system in place lacked basic cohesiveness, procedural guidelines, or a shared vocabulary. Perhaps technology would first need simply to regularize the administrative structure itself.

A decision about whether to follow the “artificial intelligence” (machine-learning) route came to the fore around the time of the February 1967 Ford board meeting. At that moment, the justification for a “total information system” on the artificial intelligence model was simply not compelling enough to merit the hefty cost. That spring, the Foundation would instead begin to implement a more limited data processing system, focusing foremost on structural continuity across the Foundation’s programs and departments. Administrative analyst Philip A. Kemp argued that, while not as cutting-edge as a total management system, it would still “provide more effective administrative and grant information than our present limited manual procedures.” (April 19, 1967 memo, RAC.)

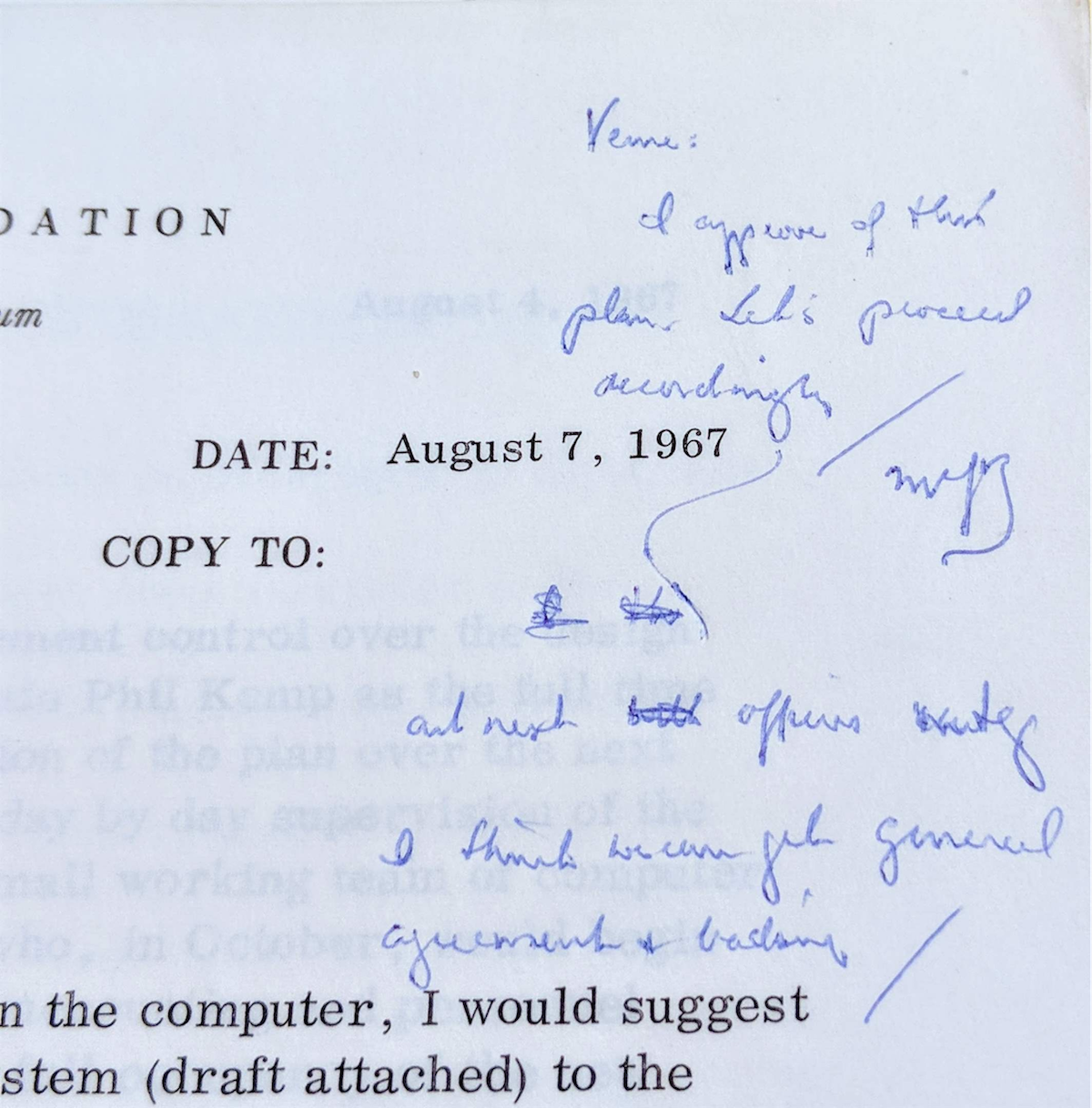

The Administration Office drew up a plan, outlined in a memo Atwater sent to Ford Foundation President McGeorge Bundy. Ironically, the latter’s approval came in the form of a hand-written note on the memo itself (pictured below)—evidence of what Philip Kemp referred to as “limited manual procedures!”

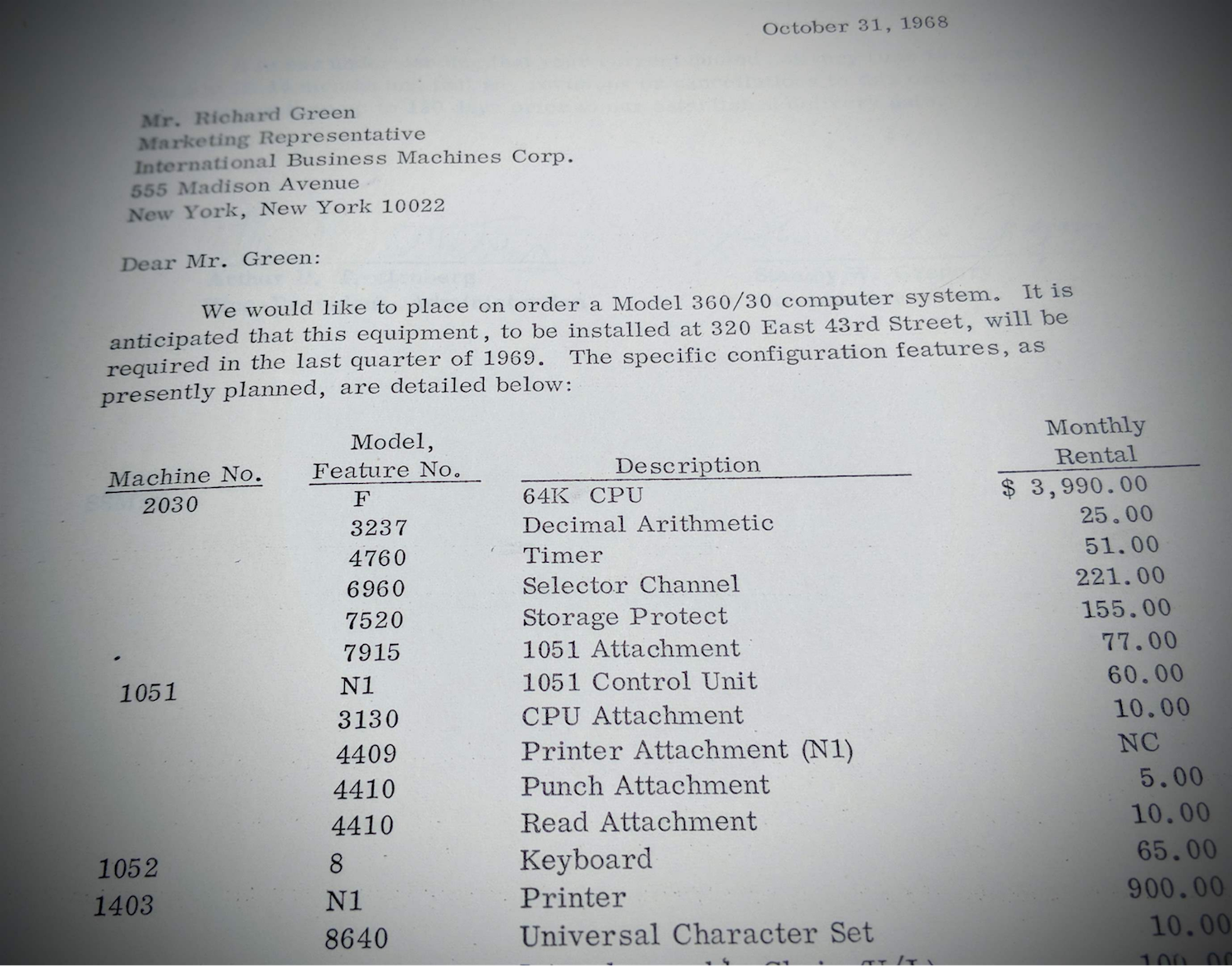

All of this was happening as the Foundation made plans to move into its sparkling new headquarters on 43rd Street. If Ford was to develop in-house computational capacity, space would need to be found (it was, on level B) and equipment procured. Ford administration decided to rent the basic equipment, an IBM 360/30 model, at the rate of $3,990 per month. That’s approximately $28,000 in 2018 dollars. If my calculations are correct, the mainframe’s 64K processing capacity, which would record basic descriptive facts about grants and grantees in the form of number codes, would amount to approximately .000032 the processing capacity of today’s average iPhone.

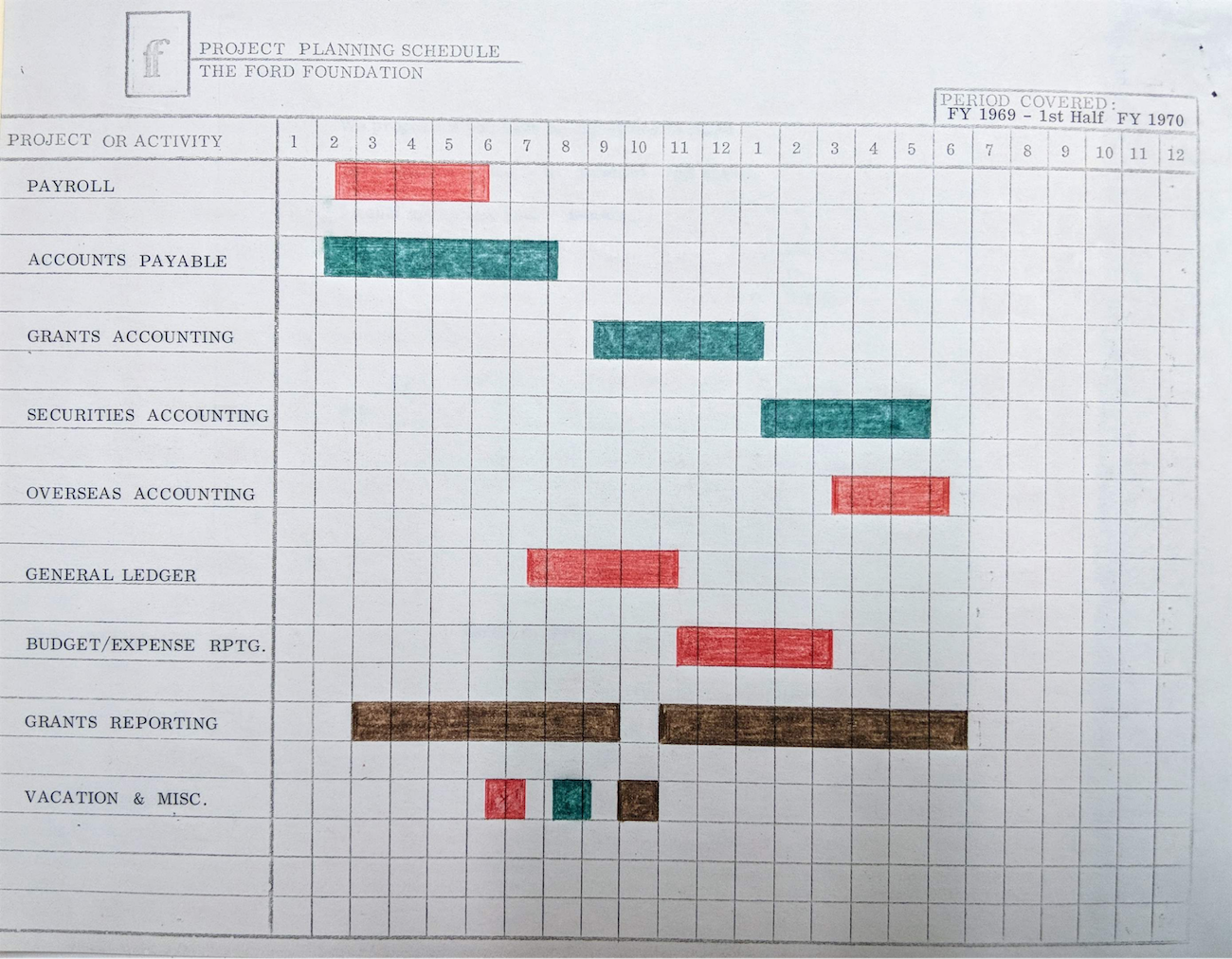

Furthermore, Ford would need to add specialized staff members to support the new system: keypunch operators, computer programmers, and systems analysts would join the Foundation in short order. And then, of course, staff in all departments would need to be trained (one hand-colored training schedule is reproduced below).

From 1969-1976, Ford staff continued to reevaluate its computer needs. New grants information systems were tested, evaluated, and replaced. In 1976, frustrated Ford administrators proposed removing the computer system entirely and using outside vendors for all data processing. National Affairs Social Development program officer (and self-described poet) Thomas Cooney was brought into that discussion, since he was interested in the intersection of technology and the liberal arts (he had contributed to the Computers and the Humanities journal in 1968). Many of the same issues remained as they had in 1965. Cooney’s handwritten notes from a 1976 meeting about a new “program action system” for grants management seem to echo Richard Reed’s “data processing for what?” question of over a decade earlier:

“[Management information systems] often don’t work because the disseminators of the information pay attention only to the grammar of their output and not the rhetoric.”