When I was chosen to be the 2024 Selznick Fellow at the Rockefeller Archive Center (RAC), I knew that I would have the opportunity to hone the skills I had learned as a part of the Selznick School of Film Preservation, as well as be introduced to new ones. So far, I have not been disappointed! One of the skills the RAC has allowed me to practice and refine is film inspection.

The Collection

I was responsible for inspecting and preparing condition reports for a collection of 16mm films that had been donated to the RAC over a period of a few years, beginning in 2017. Consisting of 16 films from the 1940s and 1950s, these films are a collection of home movies from the branch of the Rockefeller Family belonging to William A. Rockefeller, Jr. (1841-1922), brother of John D. Rockefeller Sr. (1839-1937), with whom he co-founded Standard Oil. These films were generously gifted to the RAC by family member Judy de la Gueronnere.

Inspecting and Assessing Condition

As providing access for research purposes is an important objective for the RAC, the goal for most audiovisual objects is to become digitized. However, because film ages, and sometimes not well—especially if the film has been heavily used and/or stored improperly—every film must be properly and thoroughly inspected. Inspection not only allows us to assess the object’s condition and address any immediate needs it may have, but, if its condition allows, to also prepare the object for digitization. During the inspection process for this collection, as with any collection, I wound through each film, taking note of any conditions present; added archival leader to the start and end of the film (called the head and tail); took measurements for shrinkage and footage; and conducted an A-D Strip test to determine the stage of Vinegar Syndrome deterioration.

Color Reversal

Most films in this collection are color reversal films. Color reversal films are films where the camera negative and the exhibition print are one in the same. Reversal film was popular for the amateur home market, because it eliminated the need for creating a positive print (the print to be projected) from the camera negative, thus making the process simpler and more cost-efficient. Reversal home movies are inherently one-of-a-kind items, making them attractive for archives to collect, if the content falls within the scope of their collection policy and if there is potential interest for researchers.

Kodachrome

Additionally, the films in this collection primarily utilized the Kodachrome color process, which Claire Suddath, writing for Time Magazine, defines as “[a process] in which three emulsions, each sensitive to a primary color, are coated on a single film base … While all color films have dyes printed directly onto the film stock, Kodachrome’s dye isn’t added until the development process” (Suddath, 2009).

The Kodachrome color process is known for its color accuracy and for maintaining its color, and, as Suddath explains, “…although all dyes will fade over time, if Kodachrome is stored properly, it can be good for up to 100 years” (Suddath, 2009). I found this proved to be true when inspecting this collection. Even in areas where the film severely curled, the image was still quite beautiful.

Condition

Overall, the condition of these films is moderate. Some films are in quite good condition, while others suffer from deterioration typical of acetate film which had previously been stored in less-than-ideal conditions. The most common deterioration I encountered was shrinkage. The National Archives’ “Glossary of Terms” for archival formats defines “shrinkage” as the following:

The difference between the present dimensions of a film and the dimensions of that film when it was produced, given as a percentage of the original dimensions. Shrinkage of cellulose nitrate and cellulose acetate film bases is inevitable and is caused by chemical off-gassing. (Archival Formats: Glossary of Terms, 2023)

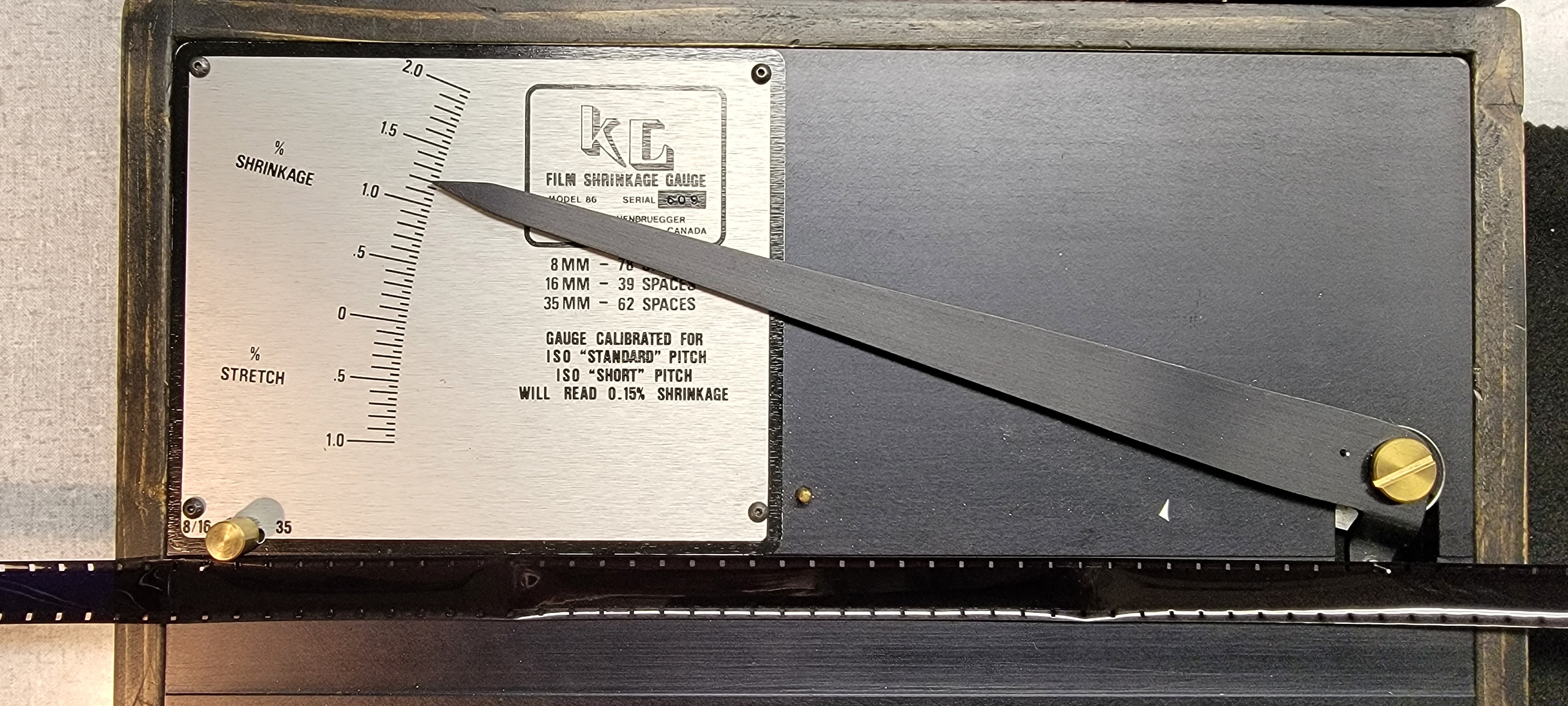

Shrinkage can manifest in several different ways, depending on the severity and how evenly the film shrinks. Acetate film is prone to shrinkage. When measuring the shrinkage of the films in this collection, more than half had a shrinkage measurement of close to, or over, 1%. This amount of shrinkage begins to affect the ability of the film to be projectable and, in some cases, scannable, as the perforation holes will no longer align with the sprocket holes of a projector or scanner. Luckily, many scanning and digitization services have methods and equipment available to allow shrunken films to be scanned, so their content will not be lost.

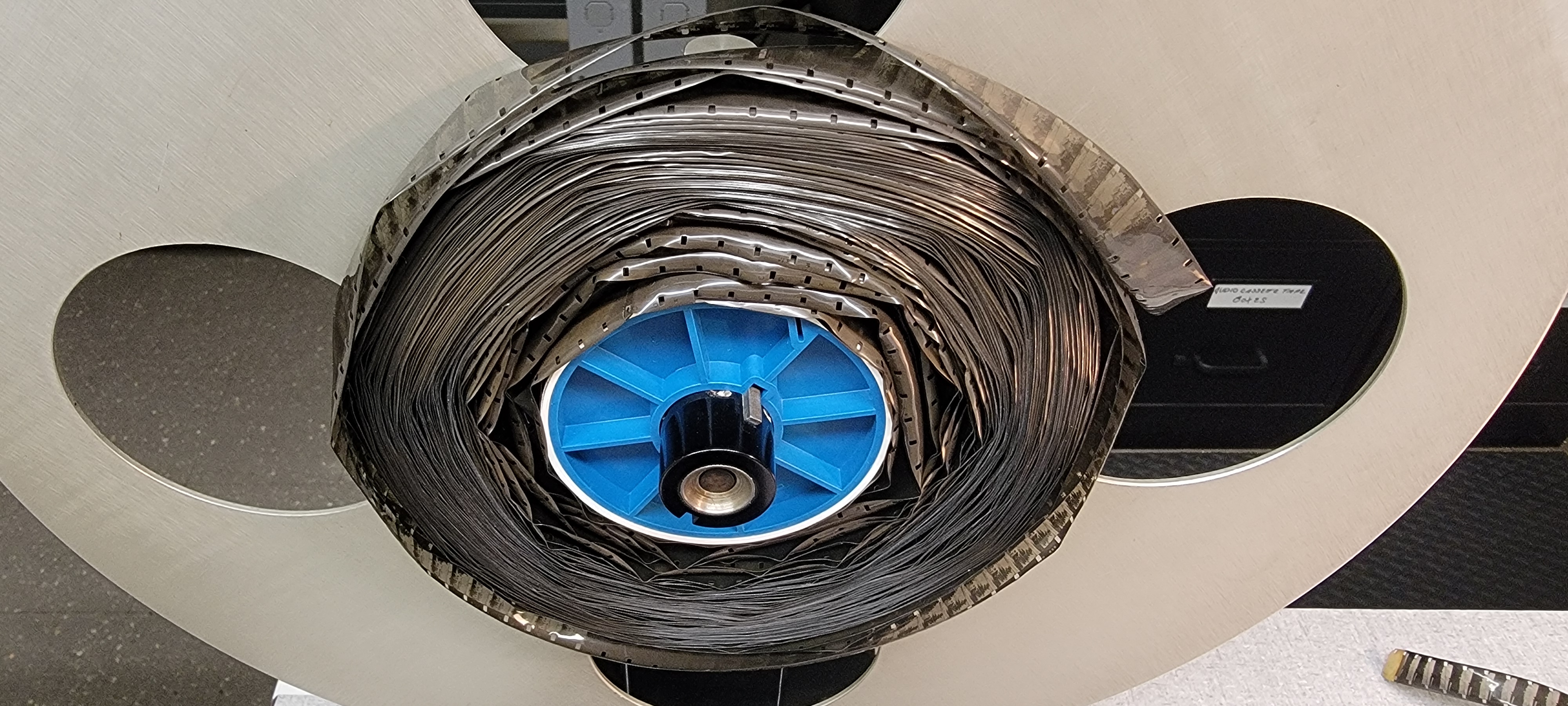

However, when film shrinks unevenly, generally because the acetate base shrinks at a different rate than the gelatin binder, it can become distorted and manifest as warp or curl in the film.

Since this material is principally affected by environmental conditions—such as temperature and humidity (or lack of it)—it’s unsurprising that I encountered severe curl in a handful of films in this collection, always primarily at the head (or beginning of the film).

The film in these areas is difficult to handle when attempting to wind the film onto an archival core, as it has lost much of its pliability and ability to lay flat.

A very loose wind is required.

The film is very stiff and requires slow and careful handling.

Fortunately, most other conditions that can typically be found with aging acetate film were not present in the films in this collection. Scratches were minimal and were mostly light travel scratches, which can occur when the film travels through a film projector. Dirt was minimal to moderate and was found around splices and at the head and tail of the films, which is typical.

Plasticizer Exudation

An interesting exception I discovered on one film – and one which I had never encountered before–was mild plasticizer exudation. Plasticizer exudation is a condition that occurs when the film base is no longer able to hold onto the plasticizer added during manufacture due to acetate decay. The plasticizer migrates to the surface of the film in the form of bubbles or crystals.

For the film with which I was working, the migrated plasticizer formed a tiny and subtle web of crystals which caused the film to slightly sparkle when moving the film around in the light. It was very cool to see, because students of film preservation, like me, learn about such conditions, but may never actually see it when inspecting a film. (Unfortunately, I was unable to take a decent picture that properly illustrated this condition.) Fortunately, mild plasticizer exudation does not affect the image at this stage, so placing the film into proper storage will arrest the deterioration until the film can be digitized.

Vinegar Syndrome

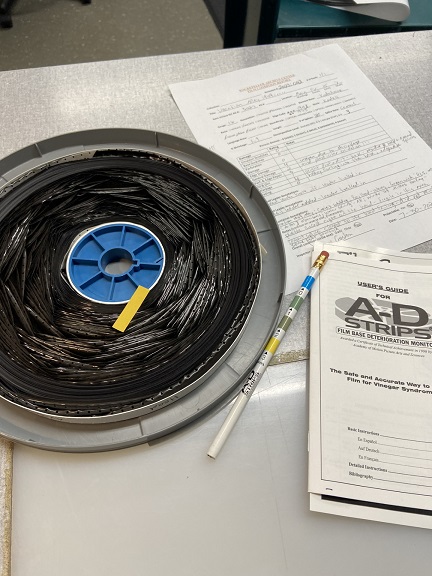

The final step to take during the inspection process is to test each film for vinegar syndrome using A-D Strips. Vinegar syndrome is a condition that occurs when acetate film begins to deteriorate. The deterioration creates ascetic acid, which smells like vinegar, in a process known as off-gassing. Films with vinegar syndrome often shrink, become brittle, and can present plasticizer exudation—all conditions that I found while inspecting this collection. As the room stank of vinegar during my inspections, I was not surprised to see that a majority of the films had a reading of 2 or 3 (3 is the highest) on the A-D Strips. (A-D Strips are dye-coated strips of paper that change color to detect the severity of acetate deterioration, or vinegar syndrome.) Because of this, most of the films in this collection have been bagged with molecular sieves to help absorb the acetic acid until the films can be placed in freezing storage.

Accession

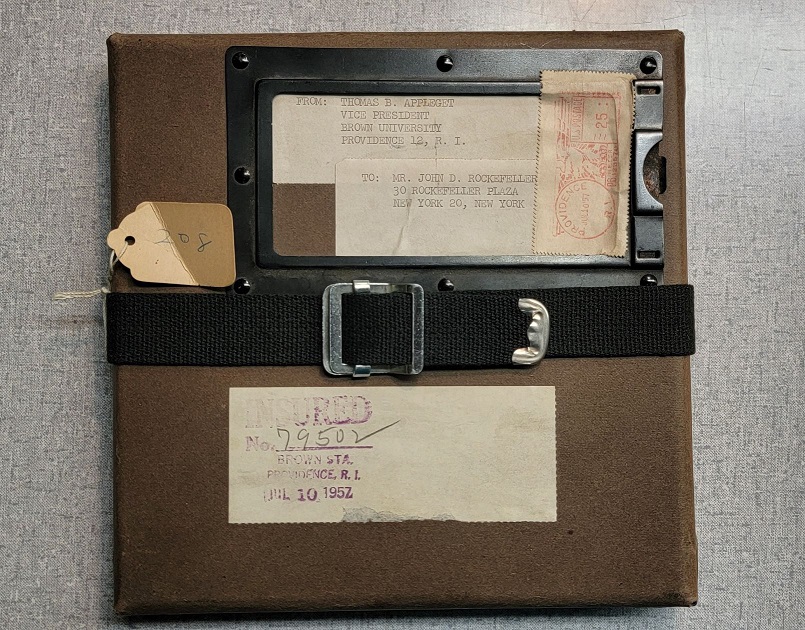

The RAC also allowed me to experience another aspect of film collection management for which I had not previously been afforded the opportunity: assessing a collection for accession. I had the fortune to join Brent Phillips, Audiovisual Archivist at the RAC, in accompanying an independent archivist on a trip to a prominent family’s estate on Long Island for the retrieval and assessment of a collection. Though this collection is outside the scope of the RAC’s collection policy, because Brent Philips, as well as I, have the proper training to assess and handle nitrate (which this collection was anticipated to be), we were asked by the independent archivist to accompany him in its retrieval, transport, and assessment. Based on the photos we were sent; we expected the films to be in an advanced state of nitrate decay.

However, we were pleasantly surprised that the films, which indeed were nitrate, were in very good condition—especially considering that these films had been sitting in the basement of a pool house for multiple decades.

Of course, the trip to Long Island to retrieve the flammable films and bring them to a blistering parking lot for inspection occurred during a heatwave (!), but at least they are now in an environment with proper storage conditions. Hopefully, the films can be restored and digitized. It was great to be a part of an assessment such as this and to use my specialized training to help in this matter.

Works Cited

Archival Formats: Glossary of Terms. (2023, October 19). Retrieved from The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration: https://www.archives.gov/preservation/formats/glossary.html

Suddath, C. (2009, June 23). A Brief History of Kodachrome. Retrieved from Time USA, LLC.: https://content.time.com/time/arts/article/0,8599,1906503,00.html