Among the many things that Aeon will do for us, communicating directly with DIMES to import data about our materials is among the most important, and a feature that will likely save both researchers and staff a great deal of time and frustration. Starting in February, researchers will no longer have to fill out requests for materials by hand; staff will no longer have to decipher researchers’ handwriting, correct inaccurate or missing information, or complete charge-outs by hand. In addition, we’ll be able to run much more accurate reports on use of our collections, which will help us better target digitization and preservation efforts. This post explains how that data moves from DIMES to Aeon, detailing some of the things that happen along the way with restrictions information and grouping of folders within the same box.

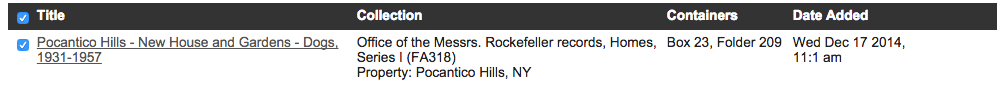

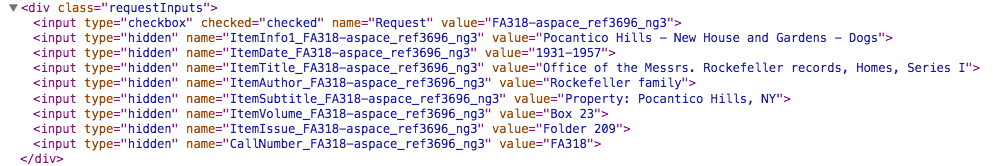

When a user adds an item to their List in DIMES, the system generates and attaches some hidden inputs containing data about that item to the page. Although these inputs aren’t visible to the user, they are the means by which DIMES sends data to Aeon. For example, here you see an item I’ve added to my List:

And this is a portion of what is generated behind the scenes:

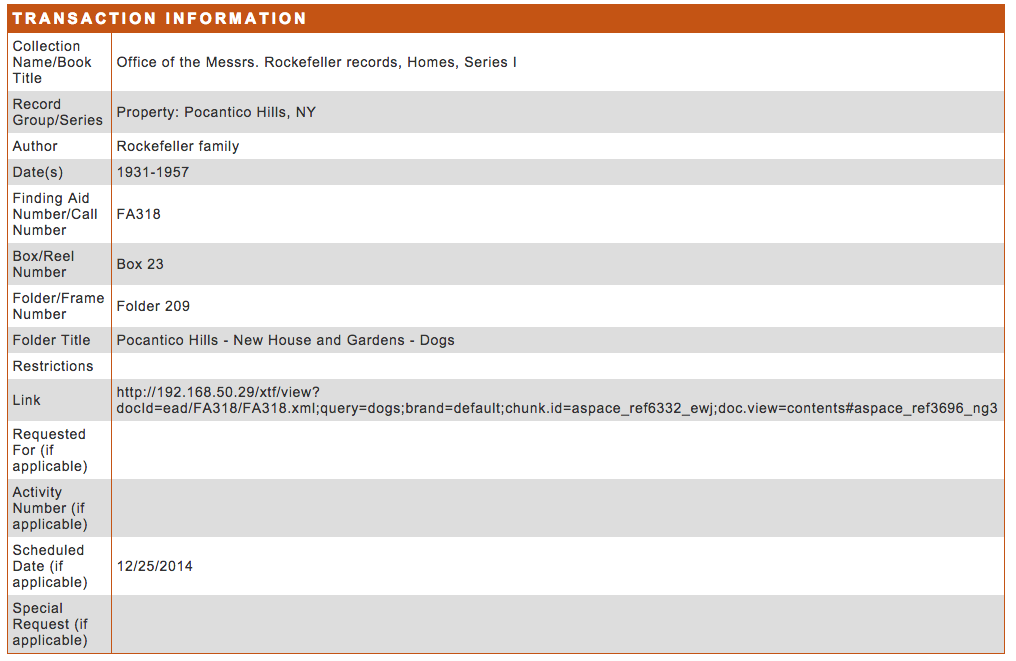

When I submit a request to see these materials in the reading room, DIMES sends this data to Aeon via an HTTP POST request. Here you can see the request as it ends up in the Aeon web interface:

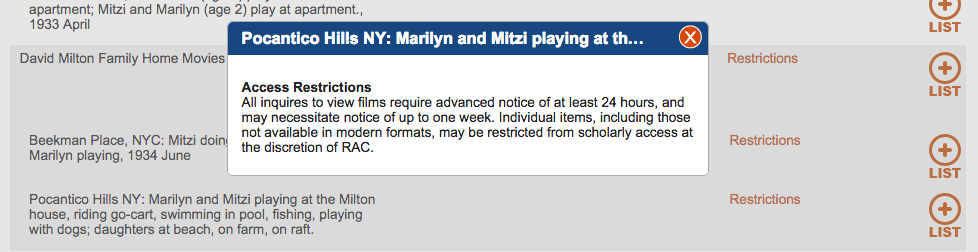

Another important thing importing data from DIMES allows us to do is have much better control over material with specific access conditions. When DIMES creates the hidden inputs described above, some special logic is applied to Conditions Governing Access notes. First, if the folder being requested has a Conditions Governing Access note assigned to it, DIMES will include that note in the information it passes to Aeon. If there isn’t a note attached at the folder level, DIMES will then navigate up the hierarchical tree of the collection to find the nearest Conditions Governing Access note. For example, if that folder is located within a restricted series, information about the restrictions from the series level will be passed along to Aeon. An important caveat to note: DIMES does not send Conditions Governing Access notes that simply document the absence of any restrictions to Aeon.

When this information is sent to Aeon, a few things happen. First, any restrictions information is stored in the system as a part of the request, and is printed on all charge-outs. Second, if Aeon notices that a request has restrictions information attached, it will route that request to a separate queue, where staff can review the specific restrictions and decide what to do with the request.

Here’s an example of a folder that has restrictions information:

That information is imported into the Aeon request:

What I’ve described above really only applies to archival materials; our books don’t have access restrictions on them and, while they may be temporarily unavailable for preservation purposes, they are otherwise always available to researchers.

Another nice feature of Aeon is that it’s able to group requests for folders within the same box into a single request, often eliminating dozens of duplicate charge-outs in a single box. It does this by referencing the collection number (or the FA number), the parent component (the series, subseries, record group, etc) and the box number of the folder requested. If that information matches for two or more requests, Aeon will group them together into a single request. This logic accounts for situations in which box numbers are not unique within a collection, for example if there are multiple series that start with Box 1.

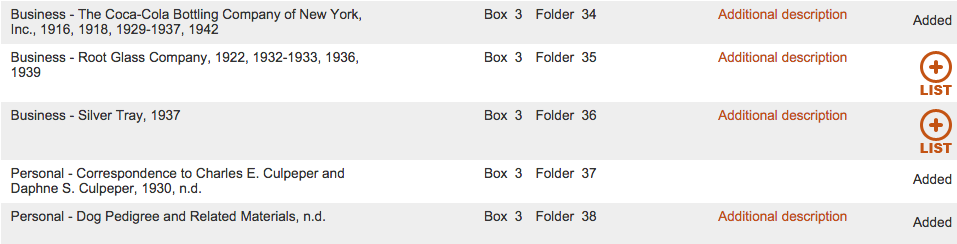

For example, when I request these three folders, which are all in box 3:

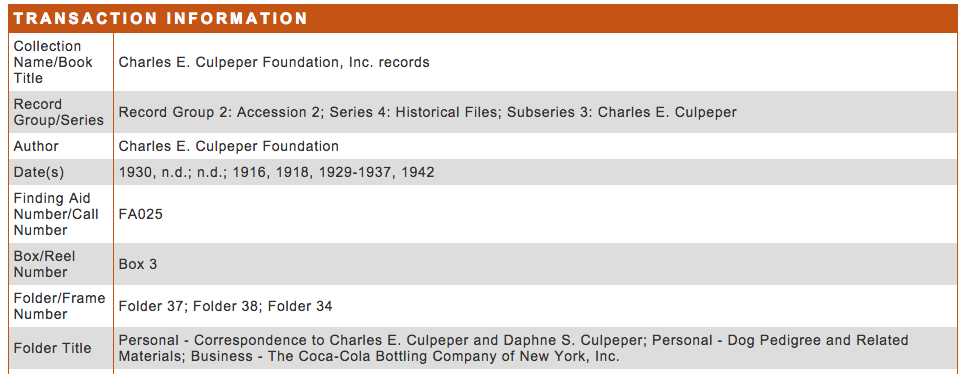

I end up with only request in Aeon that groups together all of these folders:

As you can see, the folder numbers, titles and dates for both folders I requested ended up in the same Aeon request.

All told, these changes to the ways we generate information about requests will help us provide a more reliable and efficient service to our researchers, eliminating many sources of frustration for staff with our current retrievals process, and providing a more transparent experience for researchers. It will also help us make long-term strategic decisions about access and preservation of our collections by giving us better data on which to run reports.