The Rockefeller Foundation Centennial project has made it possible for me to learn many things about the process of digitization, digital archival standards, and the construction of a website. I also have seen the decisions that need to be made so that a comprehensive, user friendly site can be built.

This project has taught me basic functional aspects of digitization: scanning, creating text-searchable pdfs, creating derivatives for images, and uploading these documents onto a website. The project has also allowed me to gain an understanding of the Rockefeller Foundation and its goals.

School children listening to lecture on tuberculosis, 1918

In a 1917 letter Starr J. Murphy writes, “man freed from the blight both of disease and of ignorance may achieve the best of which he is capable.” From what I’ve learned working with and describing the documents, this idea is the main focus of the Rockefeller Foundation and describes every effort they have made to improve society.

In going through these documents, I truly have gained a sense of the broad range of areas and projects the Foundation was interested in and funded. The history of the Foundation and the documentation in the archives is so rich and large that many of the documents did not make it onto the site. They tackled a wide range of areas: everything from Tuberculosis relief in France after WWI, to agriculture and rice crop improvements, to archaeology, arts programs after WWII, promotion of music, and funding for education in the South.

While all these documents provided me with a greater understanding of the Rockefeller Foundation and its goals and activities, I was also able to look at the 20th century through a different lens than I have before.

Planting rice, 1963

In particular, I was able to examine WWI, the inter-war years, and WWII. Through this lens of philanthropy and detailed descriptions of the activities of the Foundation I truly gained an understanding of how turbulent and dangerous this period was throughout the world.

The most interesting series of documents I came across related to Yale’s Institute of International Studies. Many of these documents dealt with international and cultural relations in the wake of WWI, and relate to studies trying to understand how international relations broke down so completely as to spark a devastating world war. In a 1931 report outlining the program, Yale professor Edwin M. Borchard writes: “the cataclysm of the War show[s] the mutual interdependence of all countries, even our own on one another.” What is so interesting about these documents is that they describe a course of study designed to prevent a global war like WWI from ever happening again. This study was trying to find some way to make the world more secure, trying to create a lasting peace in the wake of destructive warfare.

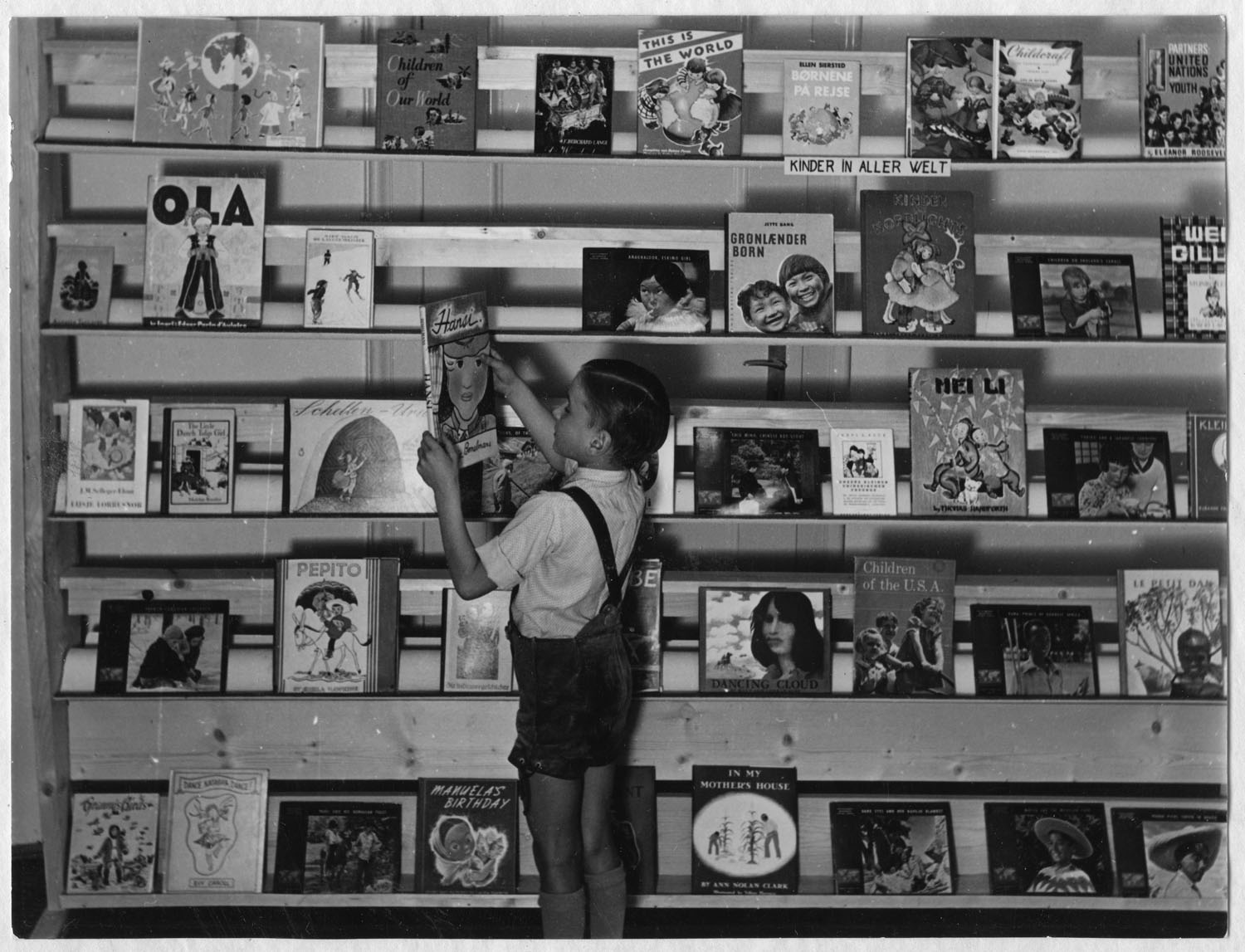

International children's youth book exhibition, 1954 (Germany)

Borchard later writes of the end of WWI: “the resulting peace conference demonstrated how great was our lack of knowledge of other nations and of our and their mutual relations.” The professors and researchers looking into international relations believed that if they could understand the causes of WWI, they could pinpoint the problems and prevent them from ever happening again.

It was a futile hope, one that we understand better now knowing that Depression and WWII were in the near future. These documents show that in the wake of WWI people did understand how destructive and devastating global war was, believed it could happen in the future, and sought to prevent this type of war from ever happening again. While these documents illuminate a project that was funded by the Rockefeller Foundation, that’s only a glimpse of what these documents contain. They not only detail the work of the Foundation, but also the feelings and worries of the time in which they were written. They give a glimpse into the 20th century and place the Rockefeller Foundation’s work in a larger context.

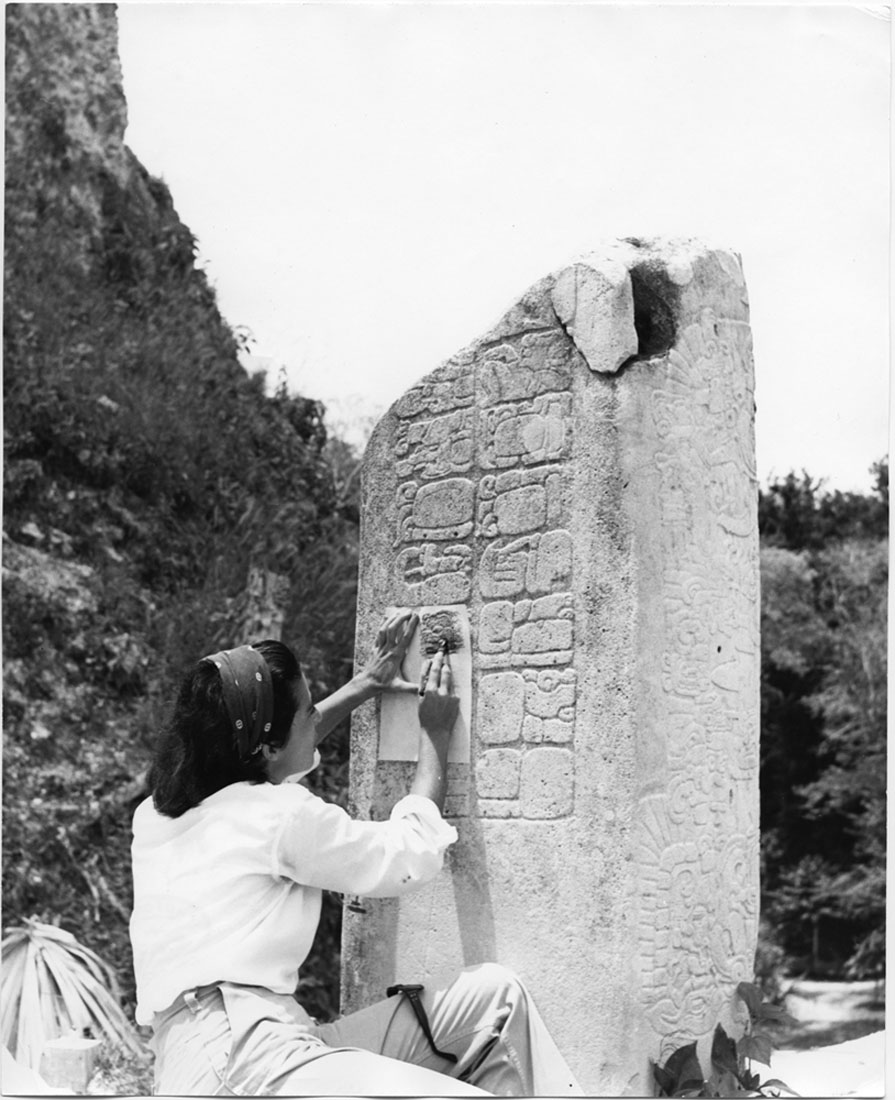

Students undergoing archaeological training taking rubbing of Maya hieroglyph, 1961 (Tikal, Guatemala)

Another interesting series of documents that I came across are the ones relating the Armenian Massacre in Turkey, beginning in 1915. This series of documents, many of which are reports, statements, or letters from people present in Turkey during the massacre, are particularly interesting because they show a historical event as it was happening. They trace the event from an undercurrent in politics and culture through to the evacuation and massacre of Armenian Christians throughout Turkey. What I found most interesting about these documents was the idea that I could trace an historical event from its beginning to the ultimate conclusion.

The papers start by saying that there was a general feeling of uneasiness in the community as men began to be taken and then started disappearing. Reverend Ernest C. Partridge writes, “We heard many rumors of massacres, but I have no evidence on the subject,” he then goes on to say, “about two months ago a general effort was carried out to imprison all leading Armenians…I estimate the whole number of Sivas men in prison to be between 1500 and 2000.” Eventually, the documents shift to a discussion about how women and children are being moved in large caravans out of Turkey, but that food and necessities would be provided for them. The accounts then move to speculation that this would not be possible and questions about the real conditions these women and children would endure.

One of the girls of the Tomato Club and her mother learning to can tomatoes, 1910 (Aiken County, S.C.)

Finally, there were pleas for help on behalf of the people being moved and killed, and accounts of how many had been killed before Americans and other foreigners were made to leave. In a letter dated June 1915, Henry Riggs writes, “What can be done to avert this catastrophe? If you can bring any influence to bear, I trust you will leave no stone unturned….We are waiting, with our hearts in prayer, and doing what little we can to relieve the awful suffering.” These documents are important because they show how a movement can grow from a feeling or an undercurrent into decisive and deadly action. I found these to be some of the most interesting documents that I have scanned and described.

So, yes, I did learn the basics of how to scan a document, create derivatives for the documents, and make it available to the public, but I also learned how the Rockefeller Foundation had an impact on society and how that impact fit into the larger context of the first half of the 20th century.