A while ago I wrote a post detailing how data in DIMES is imported into Aeon to populate requests. Since then, I’ve had conversations with several individuals asking about the technical details of this implementation. As a way of documenting that work, and also offering some direction for future Aeon implementers, I thought I’d pull together a post describing the interaction in technical terms, since there’s limited documentation on how to do external EAD requesting for Aeon. I pieced together this information by looking at existing implementations, particularly Princeton’s archival discovery system, with a lot of false steps along the way. I hope to help others avoid the same frustrations and pitfalls!

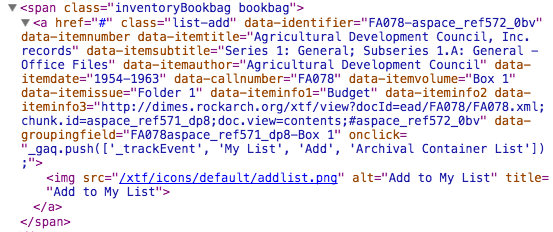

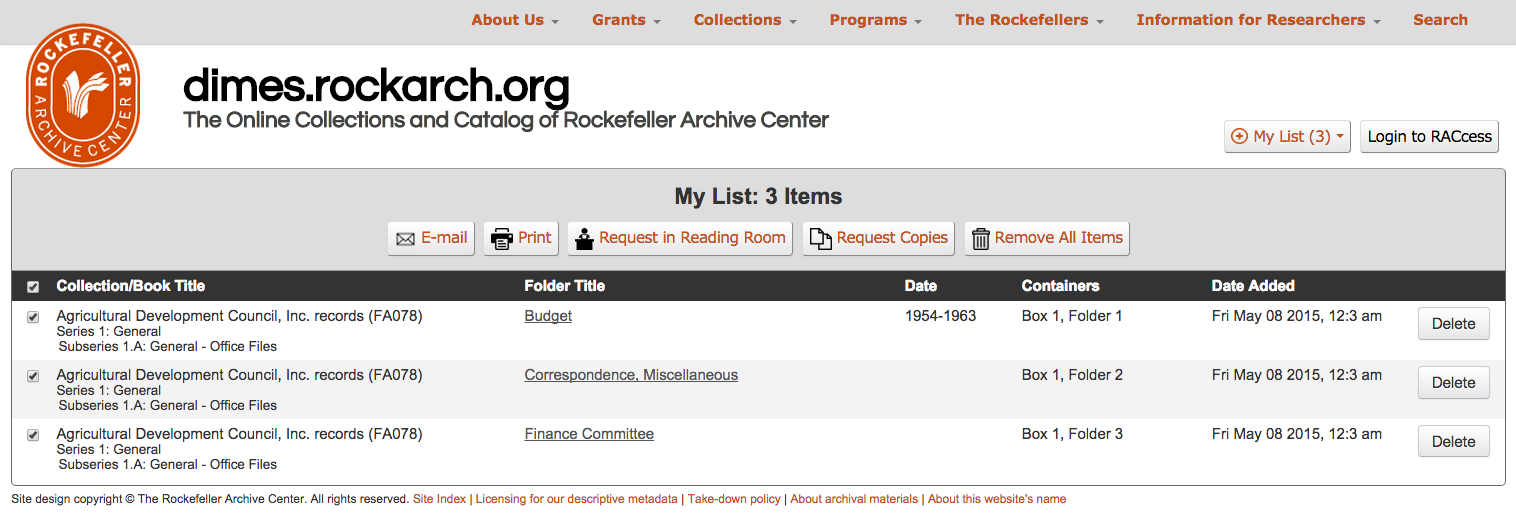

Because we were already making use of XTF’s built-in “bookbag” feature, we wanted integrate Aeon requesting into that functionality rather than building out new system functionality. On pages containing search results, library records, or EAD container lists, users are able to add individual components to their list via an “add” button [1]. They can then choose to take a variety of actions with all of these items (or a subset of them) such as printing, emailing, or making requests.

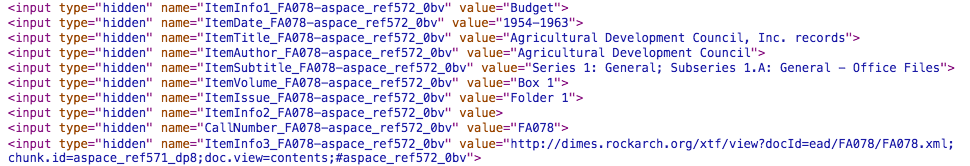

The underlying HTML for these add buttons looks like this:

As you can see, there are a number of data attributes associated with the link, which contain normalized data created during XTF indexing. Since these links need to be present in a variety of contexts, the most reliable way of ensuring consistent data was to index this data so it could be accessed regardless of whether the add button was on a search results, library record, or a finding aid page.

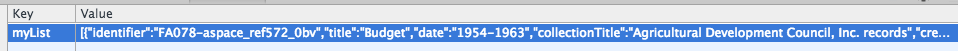

When a user clicks on this button, these data attributes are pushed to the browser’s localStorage through a simple script. The default XTF bookbag functionality works with sessionStorage, which was problematic since that data wouldn’t persist once a user closed their browser. Although there are some drawbacks to localStorage, it seemed like the best option in the circumstances because it means that data will persist in a user’s browser more or less indefinitely, and also that we don’t have to worry about the myriad concerns that come with storing users’ data.

The same script that adds data to localStorage also retrieves it, on request, to create the My List pages.

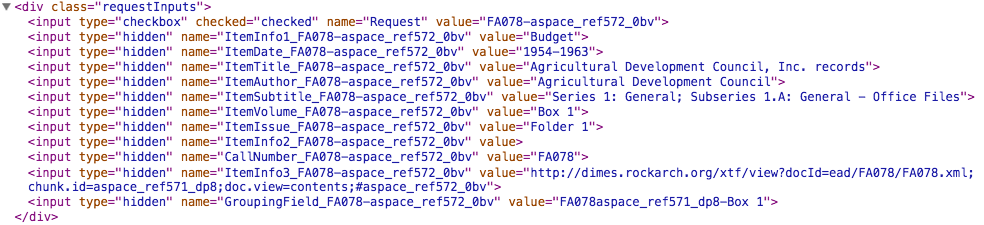

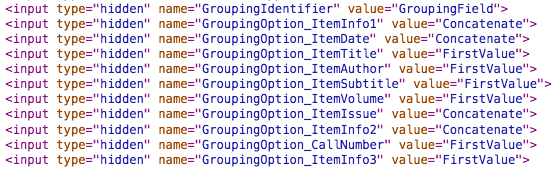

In addition to creating the HTML visible to users, this script also generates a number of hidden inputs within a form that are key to creating requests in Aeon.

Let’s look at these in some detail.

The first input simply specifies that this is Aeon request and supplies a unique identifier for that request. You can see that identifier is then repeated in each of the input name attributes in the grouping below.

The next ten inputs contain data about the component that will get imported into Aeon. The name attributes are a concatenation of an Aeon field name and the request identifier. You’ll need to set up this mapping for existing Aeon fields before you try and create requests via this form.

The last input specifies an identifier by which this request can be grouped with other requests. We’ve set this up so it’s a concatenation of an identifier for a parent component (in this case, a series) plus the box number. What this means is that all requests for components in the same box in the same series will be grouped together as a single request in Aeon, streamlining the number of requests we have to manage.

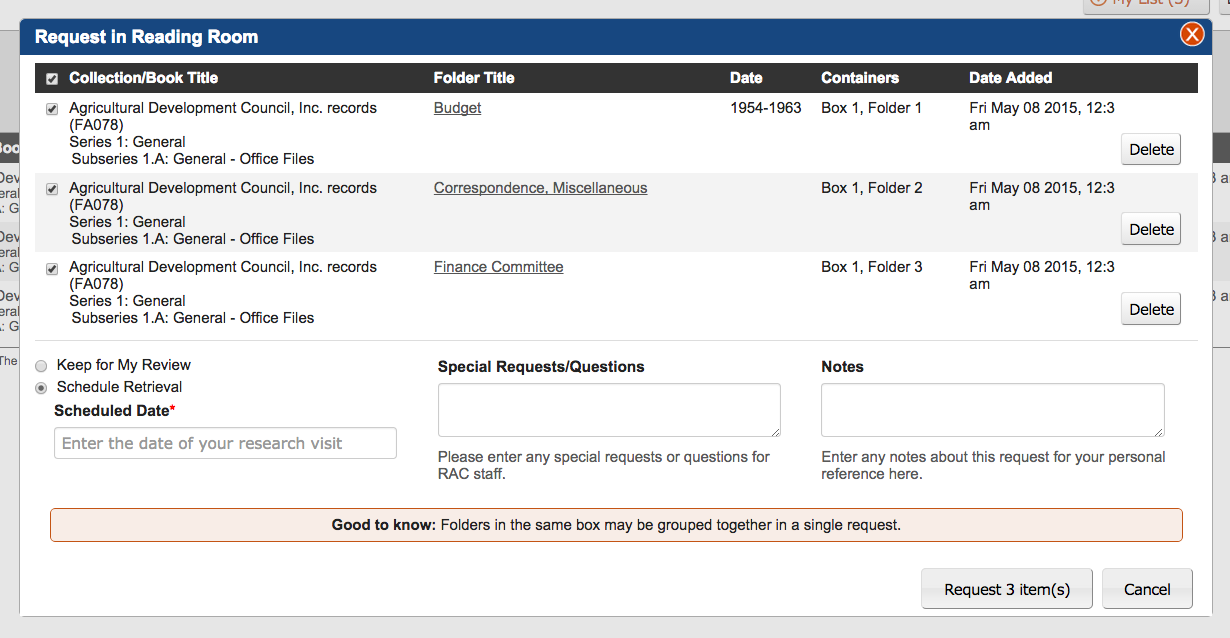

When a user selects which action they want to take with items in their list, for example creating a new reading room request, they are presented with a modal window.

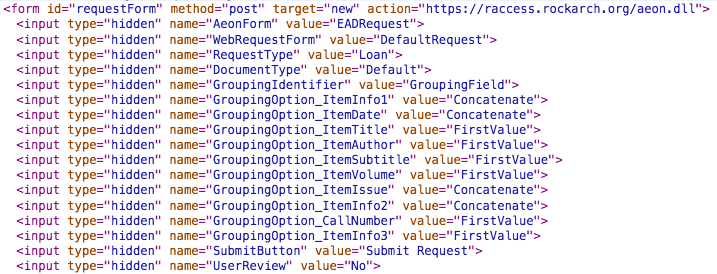

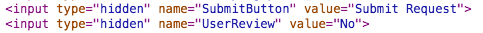

Sending a HTTP POST request to the Aeon DLL with the form data described above creates one or more new Aeon requests. Looking behind the scenes, you’ll see a number of other hidden inputs that tell the Aeon DLL how to handle these requests.

Looking at these more closely, we see three groups of inputs:

The AeonForm, WebRequestForm, RequestType and DocumentType ensure that the right kind of request is created in the Aeon database. You’d see a different value in the RequestType input for a duplication request, for example.

The GroupingIdentifier and GroupingOption fields control how information is grouped (specifically what value is used to group requests, and whether particular fields are concatenated or not).

The SubmitButton input allows the request to actually be created (kind of an important input that I initially omitted!) and the UserReview input controls whether or not the request is directly submitted for processing or is instead saved in a user’s Aeon account for submittal at a future date.

You’ll also notice on the modal window there are fields for the scheduled date as well as Special Requests and Notes. Those get submitted along with the request data as well.

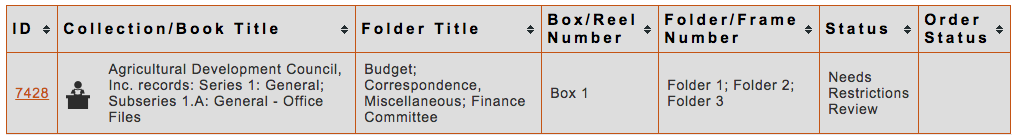

The Aeon DLL parses this data and creates new requests based on the data it receives.

In this case, all three items I requested have been grouped into a single request since they are all from the same box. You’ll also notice that one of the folders had restricted material, so this request has been routed to an “Awaiting Restrictions Review” queue in Aeon, where an archivist will review and make the necessary adjustments to the request based on the specific restrictions before submitting it for processing.

The code for all of this is online in our newly-public XTF repository. I’m always happy to answer questions about this functionality, so please reach out if you have further questions about our implementation of EAD requesting in Aeon.

[1] Important note: users can only add components that have some sort of instance associated with them (like a box and folder number, or a microfilm reel). They can’t add entire series or things without box and folder numbers. While this is slightly problematic, the alternative could present some serious challenges in terms of retrieval, so this seemed like the lesser of two evils.