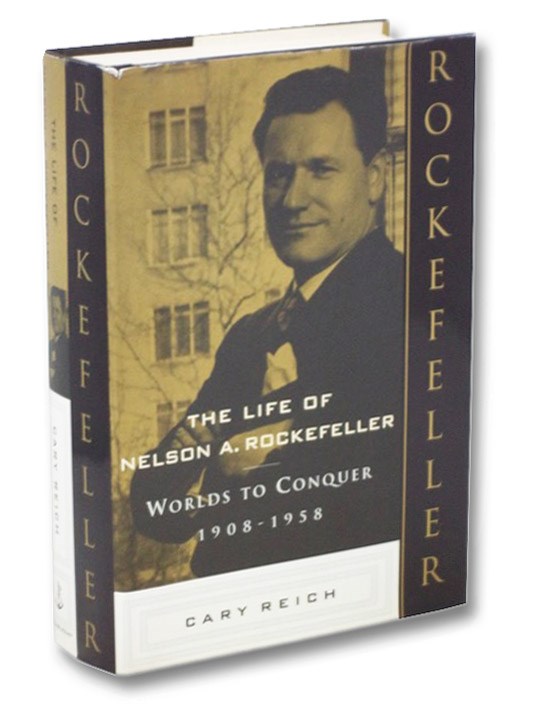

Author Cary Reich published one volume of a biography on Nelson Rockefeller, The Life of Nelson A. Rockefeller: Worlds to Conquer, 1908-1958 (Doubleday, 1996). The Rockefeller Archive Center was gifted 564 audio cassettes that contain all of the interviews Reich conducted, including recordings with the likes of Donald Rumsfeld, Henry Kissinger, and former US President Gerald Ford. However, these tapes were poorly annotated which created identification, description, and access challenges.

The Project

As someone beginning a career as an audiovisual archivist, the 10-week summer Selznick Fellowship at the Rockefeller Archive Center has been incredibly beneficial. I’ve gained valuable experience and knowledge about the practice of audiovisual archiving and the day-to-day functions of an archive more broadly. I have been able to work on multiple projects during my time at the RAC, but there has been one project that has stood out: the Cary Reich Audio Cassette Project.

When I tell people what I do for a living, most people have no idea what an audiovisual archivist even is – and if they have some idea, they never fully understand the breadth of what we do. Most people tend to think we just deal with “movies,” so it is always good to take an opportunity to discuss other material with which a/v archivists work.

To provide some background on the project, Mr. Reich had published one volume of a biography on New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller, The Life of Nelson A. Rockefeller: Worlds to Conquer, 1908-1958 (Doubleday, 1996), and was working on a second volume when he passed away in 1998.

The RAC was gifted 564 audio cassettes that contain all of the interviews Reich conducted for both volumes, including recordings with the likes of Donald Rumsfeld, Henry Kissinger, and former US President Gerald Ford. However, these tapes were poorly annotated, which I’ll get to later.

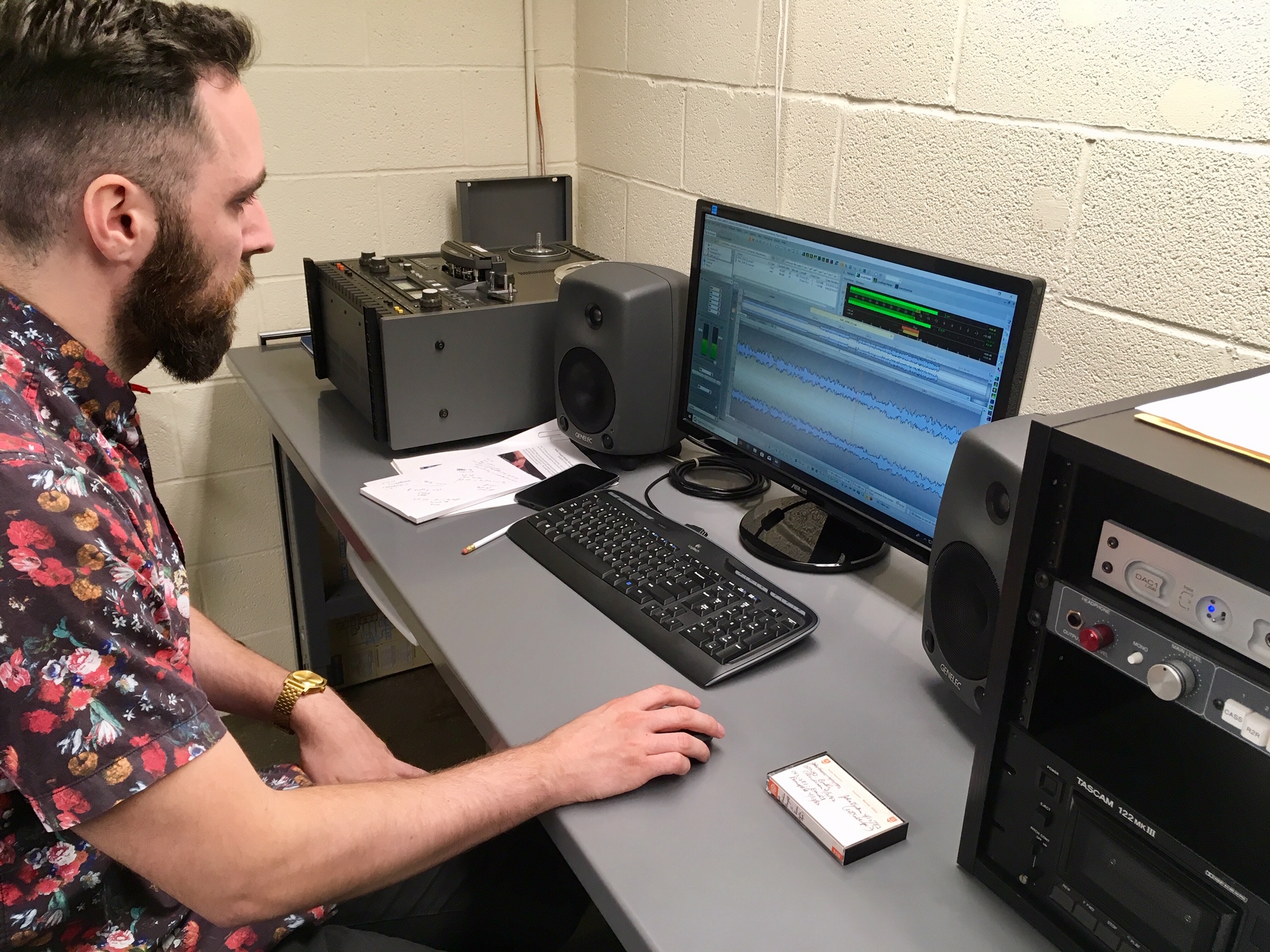

I picked up the project at the point where almost all of the audio cassettes had been digitized as WAV 96kHz/24-bit files with mp3 access copies, and a basic EAD finding aid had been created. But the files needed to be quality checked and uploaded to the RAC’s Virtual Vault for user access. Additionally, the collection’s on-line finding aid needed to be updated with pertinent descriptive information. So I was tasked with listening to each digitized audio file ranging from 10 minutes to more than five hours in length, as well as cleaning up and updating the Cary Reich papers finding aid with technical and biographical information for more than 300 resource records. As someone with a background in history, I have thoroughly enjoyed listening to the recordings and using the contextual clues found within the interviews to do research in order to discover who each interviewee is, as well as what their relation was to Nelson Rockefeller – and their connection to the history of New York.

The project has been particularly beneficial in giving me experience in devising an efficient and effective workflow and then evolving that workflow as needed. Inspecting film tends to be rather straightforward, so it’s been great to get experience with another aspect of the profession and to think through and execute a project’s workflow and goals.

Like any project, there has also been some curveballs thrown my way. But these issues have forced me to think critically in order to figure out solutions, and one of the most rewarding aspects of the project thus far has been figuring out those solutions. Of course, having RAC’s Audiovisual Archivist Brent Phillips around to run ideas by and get guidance from has helped immensely.

Annotation v. Scribble

The main issue with the project has been trying to figure out who is interviewed on each tape. Many of the tapes have multiple people recorded on them, as Reich tended to re-record over previous interviews, leaving areas of partial interviews (usually at the ends but sometimes scattered throughout) on the tapes. And even though Reich put notations on the tapes, many of the tapes have multiple names on them, with some of them scribbled out, and the names can be difficult to read.

I have, however, developed strategies that have allowed me to be successful in identifying the majority of the people on the tapes and figuring out who exactly they were. The biggest advantage is having the physical tapes on hand and being able to try to read the names written on them. As I make my way through the project – and becoming familiar with the names of the people Reich interviewed (as well as Reich’s “unique” handwriting) – it became easier to decipher the writing on the tapes. It becomes more difficult when there are two people on the audio file, but five names are written on the tape. However, once I am able to figure out who exactly is on each tape, I’m able to listen to that person’s “main” interview file and compare the voices as sort of a verification process.

If I’m unsure of what the writing on the tape says, I listen for context clues within the interview to help guide my Internet searching. A lot of the time the person will identify his or her relationship to Nelson Rockefeller, such as what position(s) he or she held within in his administrations. Not many, but a few have even said their first or last name as they told an anecdote.

Another aspect of the project has been updating the finding aid with information about the interviewees’ relationship to Nelson Rockefeller. The main sources of information I’m finding being helpful are obituaries, newspaper articles, and book excerpts. The appendix of Reich’s first biography also lists all the people interviewed for that volume along with a brief description of that person’s relationship to Rockefeller. This has been quite helpful, but I have tried to expand on those descriptions for the finding aid. To a lesser extent, I’ve found links to archival collections at other institutions to provide biographical information about individuals.

A good example of using interview clues to craft a search in order to eventually identify the interviewee and his or her Rockefeller relationship is Gene Case. When I got to this recording, the individual was only identified as Case in the finding aid. While listening to the tape, the man kept discussing commercials, so I began crafting searches around that, eventually coming up with “case, republican, political commercial, 1960s,” which lead to the Wikipedia page for the Daisy Advertisement, which was a controversial political ad by incumbent President Lyndon Johnson’s campaign during the 1964 presidential campaign. On the Wikipedia page, there is a section about the advertisement’s creation which identifies a junior copywriter named Gene Case as being one of the men on the team responsible for creating the ad. From there, I was able to navigate to Case’s Wikipedia page in order to determine that he created ads for Governor Nelson Rockefeller’s 1966 re-election campaign.

Spelling Matters

Another recurring issue has been that sometimes the name associated with a particular tape is spelled incorrectly in the finding aid. This tends to become clear when the search results are not relevant at all. When this happens, simply going to look at the tape has been the best solution, as again, I’ve gotten familiar with Reich’s handwriting and can therefore make an educated guess on a different spelling. Sometimes, though, it takes crafting different searches based on the context of the interview in order to identify the person. An example of this is Charles Percy. The finding aid record for Mr. Percy identified him only as “Perry.” Initial searches didn’t lead anywhere, but as I was listening to the interview and scouring the Internet, the interviewee mentions he was a senator. Then, he mentions he joined the United States Senate in 1967, so I looked up the list of senators from that year. There was no Perry, but I found a Charles Percy from Illinois, whose Wikipedia page identified him as a Rockefeller Republican. From there, I was able to discover that he also worked on the Rockefeller Brothers Fund Special Studies Project.

Discoveries like that are super rewarding and give me that shot of motivation to keep going and push through the next road block that inevitably comes. Also rewarding has been the opportunity to personally digitize some of the remaining audio cassettes in-house using WaveLab software. Having executed an audio digitization workflow – and having become familiar with another piece of digital software – is going to be beneficial for my skillset as I go out into the workforce. It also gives me the satisfaction of making more material accessible for researchers.

As I near the end of my fellowship, I am hoping to make it through all of the audio files and get all of the Cary Reich finding aid records updated. If I do not, though, I will be able to leave behind a workflow document to help the next archivist pick up where I left off. In my brief time in this profession, I’ve discovered that leaving a proper guide for the next person is incredibly important because as a frustrated archivist once said to me, “A lot of this job is cleaning up the mess people before you have left.”