Below is a talk that Bonnie, Patrick and Hannah gave at the 2018 NDSA Digital Preservation Conference in Las Vegas. It has been edited slightly for the blog format. Our slides are available online.

Introduction

I’m Bonnie Gordon, and with me are Hannah Sistrunk and Patrick Galligan. We’re all on the Digital Programs team in the Archives unit at the Rockefeller Archive Center. Our primary collecting area is philanthropic foundations, and many of our donors are current organizations of varying sizes. Our archives unit is made up of over 30 staff spread out over 5 teams: Reference, Processing, Collections Management, and the D-Team, which is the 3 of us plus the Head of Digital Programs. Our team was initially formed over 5 years ago to handle everything “digital,” but has evolved from working on operational digital preservation and digitization activities to overseeing projects that allow our organization to implement a sustainable digital preservation program, described in our mission statement as providing technical support and leadership to our colleagues.

Values

Important to our work is a set of 7 values that we’ve created and evaluated over time. The overarching value is to “engage and empower users,” but they are also around providing ethical access, collaboration, and creating a culture of learning. These inform all of the work that we do, including the projects we’re going to talk about.

Project Electron

This talk centers around Project Electron, which is an initiative we have undertaken at the RAC in partnership with Marist College to build sustainable, user-centered, and standards-compliant infrastructure that supports the ongoing acquisition, management, and preservation of digital records. It is open-source, with the code and supporting materials available on the RAC’s GitHub.

Project Electron was conceived of in anticipation of an increasing volume of ongoing and regularly scheduled transfers of born digital records from our donors. In the past we’ve done some ad-hoc accessioning of born digital records, but had not implemented a holistic born digital records program. This initiative represents a substantial change in the way our organization will manage archival records and in our relationship with technology, which is what we want to focus on in today’s talk: How we are managing the organization’s transition in the development and implementation of Project Electron?

Just as we have values that guide our work as a team, we have defined 4 project values for this initiative. I want to ground our presentation by highlighting those values here. These are available with greater detail on the Project Electron website.

- Create reproducible and modular deliverables

- Place users at the center of the design process

- Support archival practices and standards

- Support data in motion

So with this introduction to the context and values that drive our work, we’re each going to share some of the approaches we have taken in designing and implementing this new infrastructure in ways that are enabling us to transition successfully.

User-centered design - Hannah Sistrunk

My work emphasizes a usability and user experience approach to what we do. You saw in the Project Electron values I shared that one of the values is “placing users at the center of the design process”. I’m going to get into some examples of how we have done that specifically with our staff users at the RAC. Implementing Project Electron means bringing new processes, workflows, and required competencies, so involving our staff users in the design process has been central to our strategy of building infrastructure that is sustainable and that our colleagues understand and are invested in.

I’m going to describe some participatory design activities and approaches we took in developing an application that enables the transfer of born digital records from our donors to the RAC. These activities include creating personas, scenario mapping, and usability testing that all helped shape the requirements for this application as well as influenced user interface design decisions.

Aurora

Project Electron includes the development of Aurora, which is the web application that enables the ongoing transfer of digital records from our donor organizations to the archives. We also have a set of microservices that move data between Aurora and our archival management and preservation systems. Before I get too deep into the design process, I want to quickly introduce you visually to Aurora, which is really a central piece of the Project Electron infrastructure.

With the transfer of records, the application virus checks and validates those transfers as they come in using the BagIt specification. It also enables appraisal and accessioning of those records by archivists, as well as creating rights statements using the PREMIS standard that are automatically applied to records based on record type as defined in the transfer metadata. I won’t go too deep into the specifics of this application now, but again it’s open source and available on our GitHub.

Creating personas

In the project planning stages the team did a set of interviews with the various user groups of Project Electron to develop the project requirements. Shout out specifically to Hillel Arnold, Bob Clark, and Margaret Hogan Snyder, who completed this important work. The specific user groups include the Rockefeller Archive Center staff, our on-site and remote researchers, donor organizations, and individual donors. Based on their interviews, they created user stories to identify specific end-user needs. User stories break down into the who, what, where, when, why and how as simple statements. For example “As an archivist, I want to create an audit trail of events associated with a group of digital records so that I can ensure their authenticity”.

With these user stories in hand, we involved staff from various program areas to do an open card sort activity where they created categories for and grouped the user stories into general personas and filled out some basic persona templates of who those people might be. In the end, there were a total of 12 personas in three groups: donors and depositors, researchers, and information professionals. The personas were then fleshed out more fully like persona Nashmia Khan, a records and information manager, to include her background, goals and motivations, needs, pain points, and technology profile. As representatives of our user groups, these personas have been important reference points that ground our decisions in this user centered approach that we strive for.

Scenario mapping

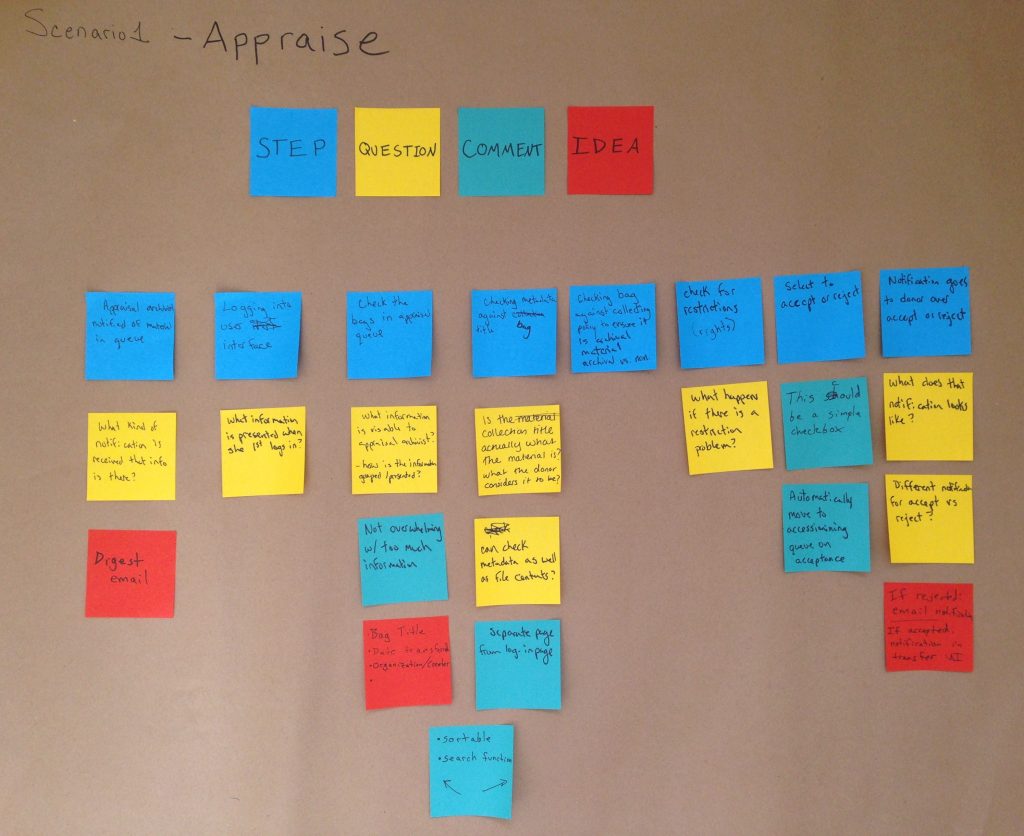

The second example of a participatory design activity I want to share is scenario mapping. Scenario mapping is an activity we did with the RAC collections management team to map the steps a user might take in traversing Aurora and trying to accomplish specific tasks in the application. The outcome informed development and design decisions based on what we learned about our colleagues’ motivations and processes.

For this activity we split into groups and each group created a step-by-step map of how a specific user would accomplish a given task including each step and any associated questions, comments, or ideas associated with that step. We used our personas for this activity.

Scenario mapping example

For example, this (see above) was a map created for a scenario that specified that Annette Johnson, an appraisal archivist, needs to make a final decision on whether to accept or reject some or all of the new transfers that have passed virus checks and validation and are waiting in Aurora’s appraisal queue. You can see the steps represented by blue colored post-its that the group came up with, and a set of associated comments, questions, and ideas represented by the other post-it colors. These RAC staff members already have domain expertise in this area from their work, and so their insights and expectations were really key for us to design something that would make sense for their workflows.

The Aurora appraisal user interface was designed based on that specific appraisal scenario, and incorporates much of the expected functionality that was mapped in these scenarios related to accepting or rejecting transfers to be able to view details and metadata associated with those transfers, write associated notes, as well as built in notifications that are triggered for donors based on the archivists appraisal action.

Usability testing

Finally, we undertook usability testing of Aurora, again primarily with our collections management team. I conducted 7 tests in two rounds of testing. The first round targeted all the major functions of the application, and the 2nd round focused on features that had usability challenges that were revealed in the first round of testing. We took a lightweight approach to testing, which was really influenced by Steve Krug’s book Rocket Surgery Made Easy: The Do-It-Yourself Guide to Finding and Fixing Usability Problems, which I recommend to folks who are getting started with usability testing.

Our testing consisted of a test facilitator (me) sitting down with a user and giving them specific tasks to try to accomplish in Aurora. The session was recorded, with their permission, and other project team members observed remotely. We made changes to Aurora between tests in an iterative approach so that we could test those changes with the next user. Throughout this process, we were able to see how users, who will ultimately be the primary users of this application, interacted with it.

Our primary goals in this process were to improve the Aurora UI, facilitate hands-on use of Aurora by staff users before the application is released and becomes part of their archival workflows, avoid top-down implementation and surprises for users, and to incorporate user perspectives and expectations into the application. These goals are centered around the project value of engaging and empowering users.

What it’s all for

These activities are all about getting staff involved in design in a way that incorporates their perspectives and expertise. They don’t need to know how to code to contribute; this provides other important ways to collaborate with our colleagues. Through these participatory design activities we are engaging the users and future maintainers of technology in its development, incorporating perspectives from across the organization, breaking down common barriers to engaging with tech development, and consequently contribute, we hope, to the long-term sustainability of this digital infrastructure.

Collaborative data modeling - Patrick Galligan

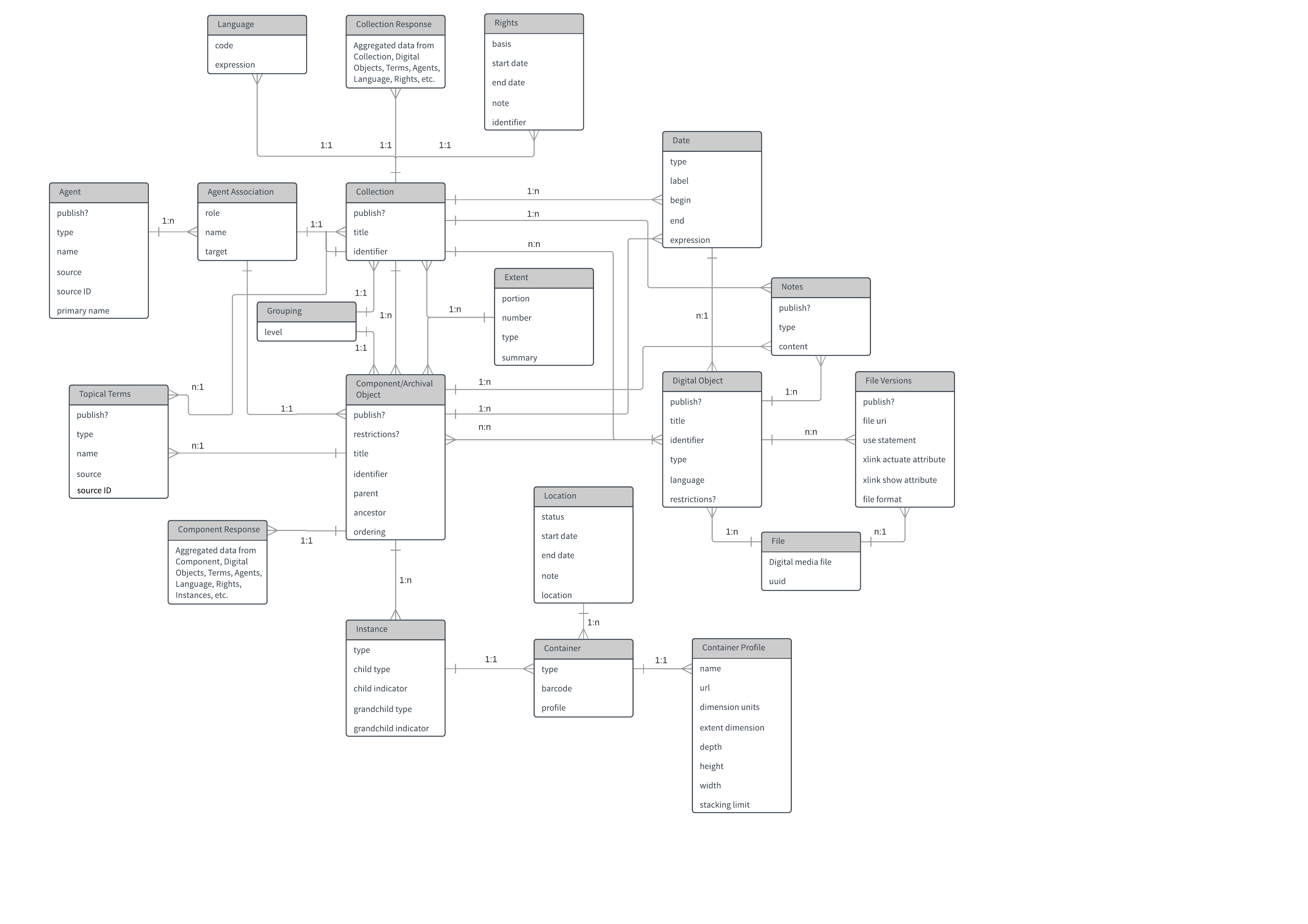

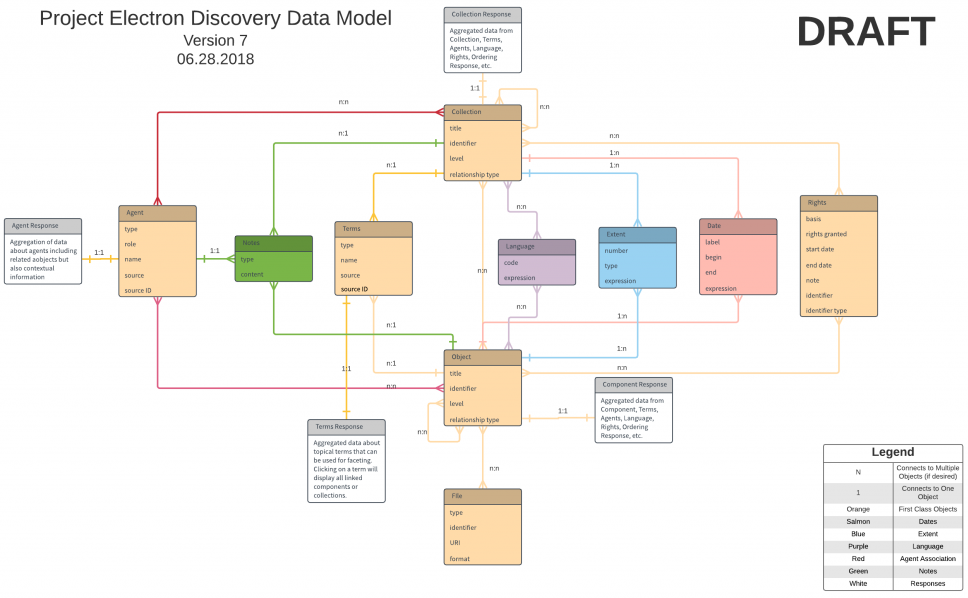

I’m going to talk about the process of collaboratively creating a data model for display and discovery of archival materials. As Hannah mentioned, one of the goals of this project is to support data in motion, and my job was to help make that happen by facilitating systems integrations. To do this we needed to pull information from ArchivesSpace, Fedora, Archivematica, and any other systems we’d need. We needed to model the way data would move between these systems. But the question was: how do we do this?

The approach

I should mention that no one at the RAC had hands-on experience data modeling before this project, so it was a learning experience for everyone involved. I ostensibly had the most experience and exposure to the concepts because I had been to a data modeling workshop at Code4Lib, but that’s about as far as my experience went.

The D-Team knew that we wanted the data modeling experience to be as collaborative as possible because it would help us produce the best possible product because others would help identify issues or inconsistencies in our work. Before we could get collaborative, I needed to make sure I understood the concepts, so I read a lot about ontologies and data modeling, and created an annotated Zotero bibliography of all the readings (link), which gave me the necessary basis to start working with others and share those resources outwards.

Introducing data models

My first goal was to get all archival staff at the RAC on a baseline level of understanding about data models and ontologies so that we could talk about them. I didn’t need my coworkers to be experts on the subject, I just wanted them to know what they were looking at and make comments on it. To this end, I led two “Intro to Data Modeling” sessions, for which I drew heavily from the data modeling 101 workshop at Code4Lib 2017 taught by Mark Matienzo, Christina Harlow, Hector Correa, and Steve van Tuyl. The workshop leaders had some great ways to frame data modeling for neophytes that proved helpful in talking about a subject that I was admittedly still fairly new to. Each intro session was about 2 hours long and a combination of hands-on group activities and me talking about data modeling concepts.

Wine

We started out with an ontology exercise in recognizing the essential characteristics of wine. Wine seemed like a perfect choice because it’s so ingrained into our society’s zeitgeist that even if you’re not a wine drinker or fan, you probably know something about it. Additionally, there are so many ways to describe wine, that it seemed like a fun way to get participants involved and invested in the session.

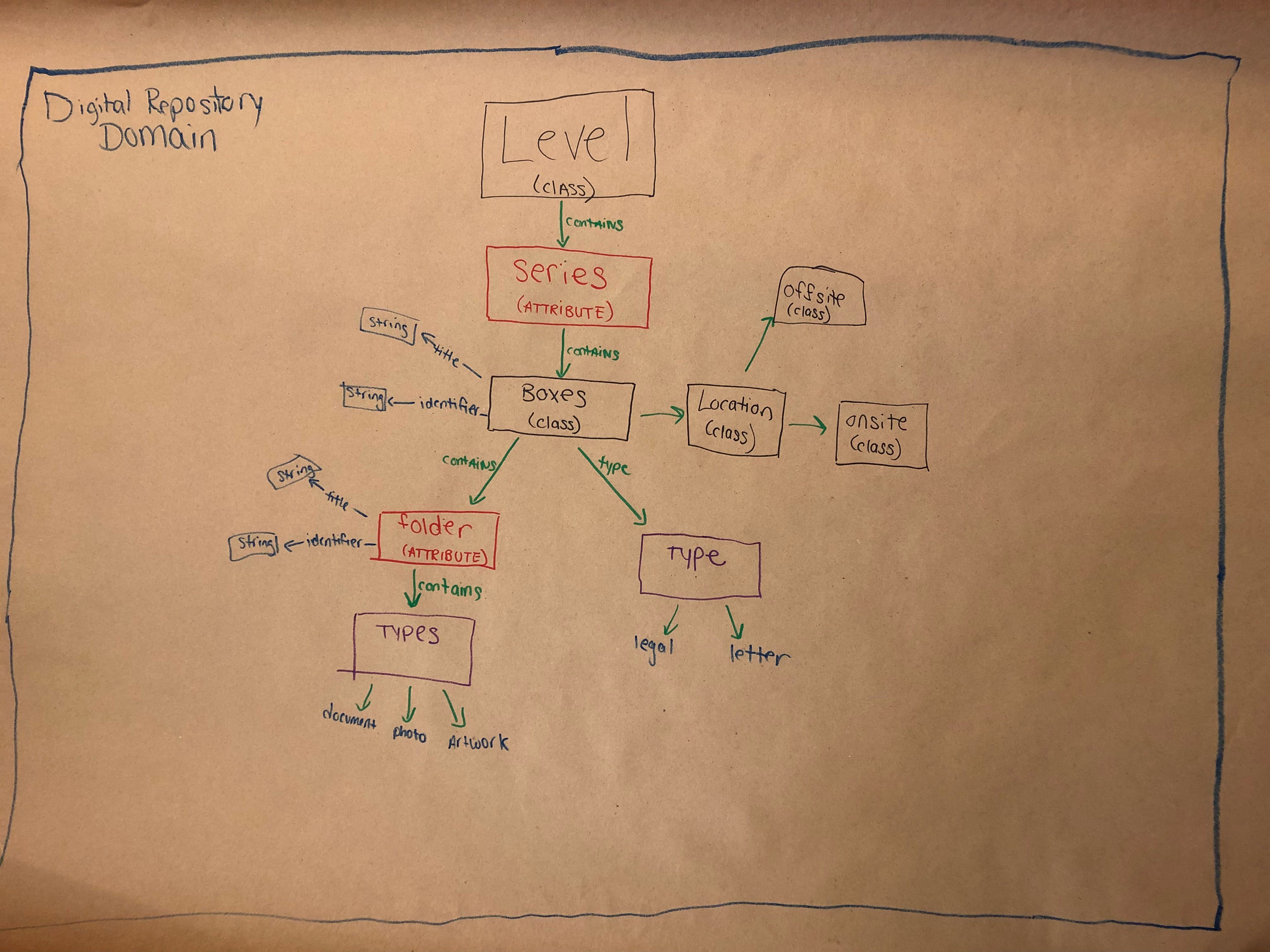

Next, the groups took a prose description of needs for a digital repository and broke it out into attributes, types, objects, classes, and functions. I took this exercise directly from the C4L data modeling course, and it worked wonders in explaining the differences between the different types of objects in a data model.

We finished off the workshops with a group data model diagramming activity. Each workshop split into three groups, chose a sample object from the RAC, and tried to draw a model of it within a digital repository.

These were first attempts at diagramming and were not used for the overall model, but I think they were admirable for groups that had no idea what a data model was 90 minutes earlier.

RAC model

Following these sessions, it was time to dip our toes into actual modeling. It’s at this point that we looked for a different community to collaborate with: our peers outside of the RAC. In particular, many thanks go out to Alex Duryee at the NYPL for sharing a general discovery data model and providing some feedback on our earlier drafts, as well as the team at the University of Michigan’s Bentley Historical Library for providing robust comments on early drafts because they had done some of this work before and we knew them well. Our goal was to build upon as many existing models or ontologies as possible so that we didn’t re-invent the wheel. Most of our modeling work started by drawing from PCDM.

First model

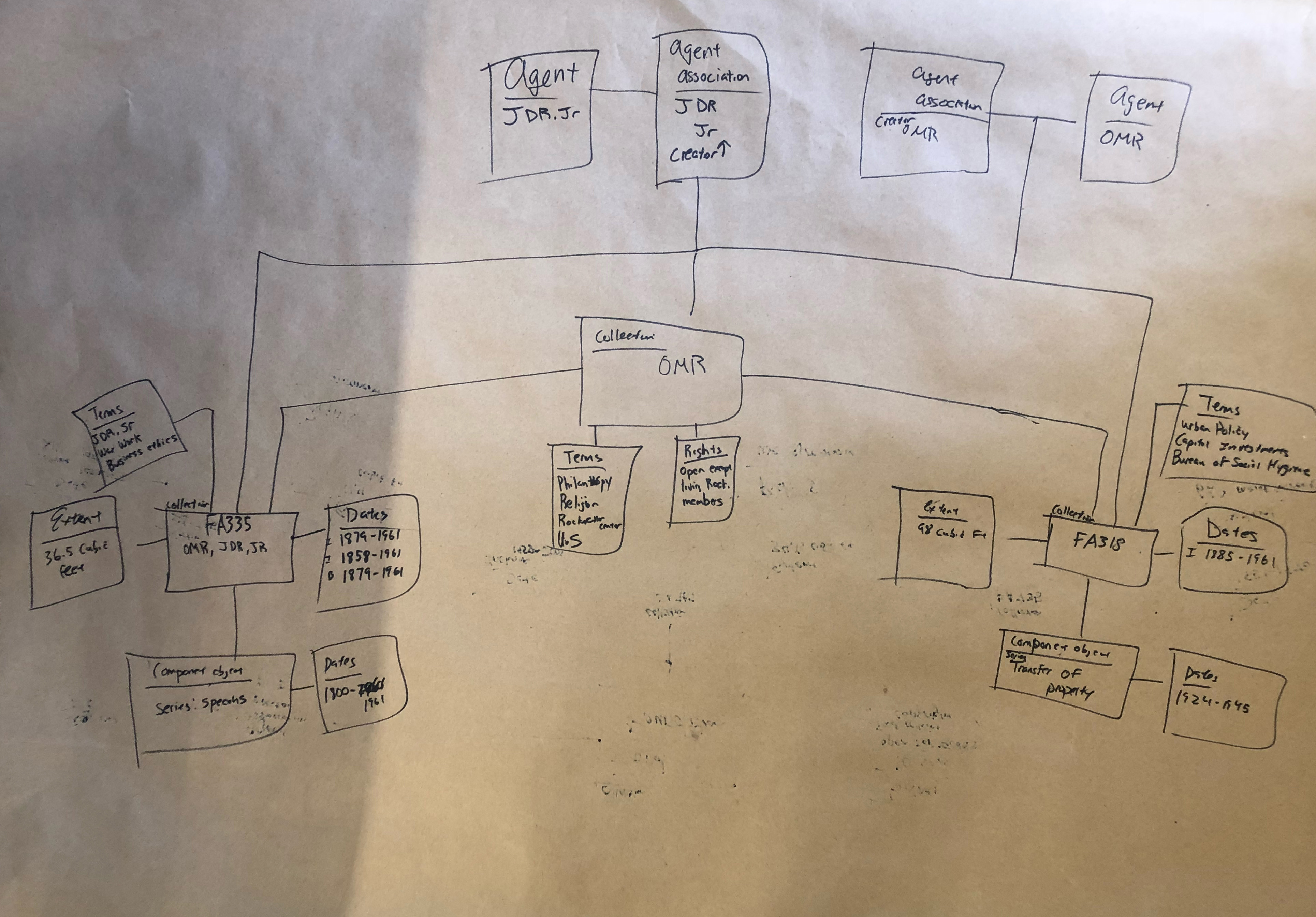

We felt this version of the model offered a valuable jumping off point for critique and review even though it looks nothing like the later versions.

Back to drawing

In late January, we started scheduling separate meetings with our Processing and Reference teams. The goals of these meetings were threefold: introduce the staff at large to our data model diagram, explain the thought process behind its creation, and finally get groups to work with it and kick the tires. Our goal was to treat these meetings as informal user tests that would ideally uncover any false assumptions we had made during the initial modeling as well as provide insight into different ways our coworkers want to interact with data.

Three tasks

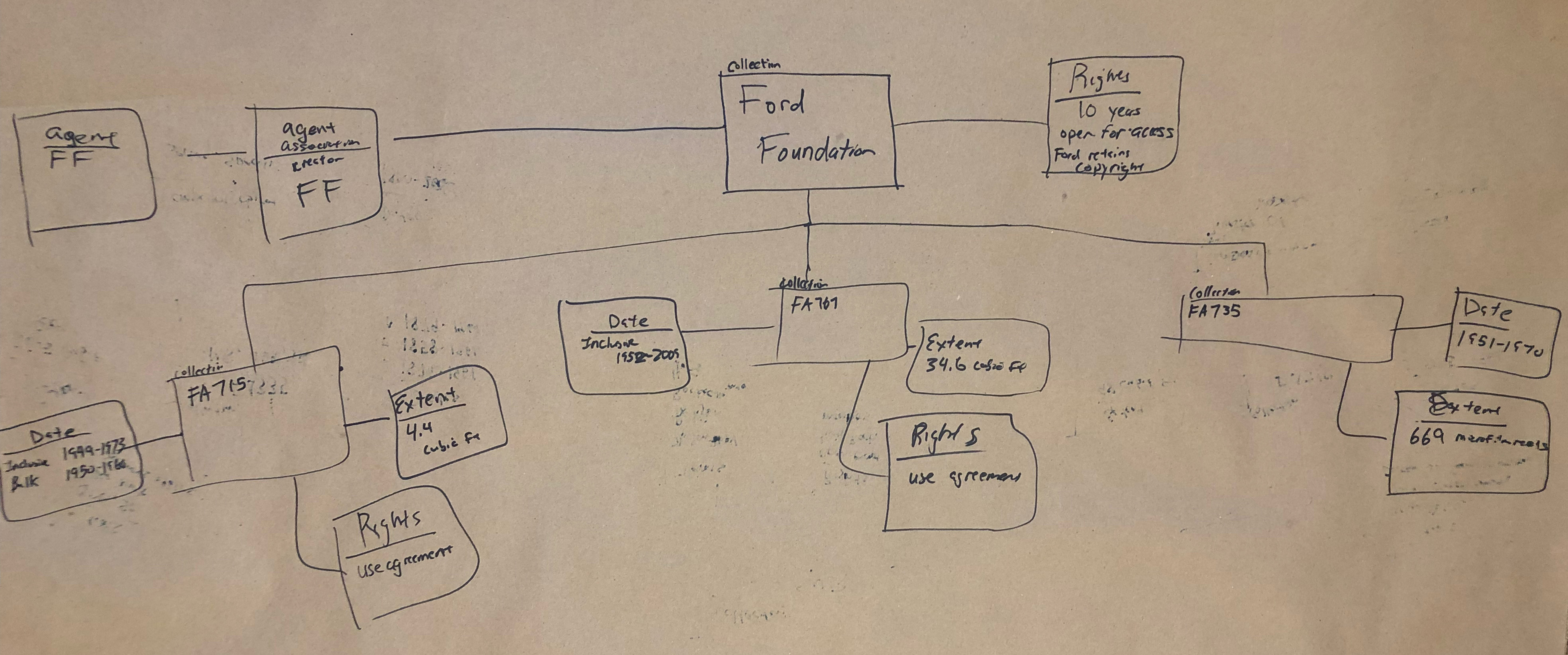

We asked the participants to break themselves up into smaller groups and then gave them three different user tasks to attempt using the data model and existing archival description as a guide. The three tasks can be summarized as:

- Use the data model to diagram data from a single finding aid.

- Use the data model and multiple finding aids to diagram data and the relationships between the three finding aids.

- Use the data model and two finding aids to diagram the data in relationship to an agent (John D. Rockefeller Jr.).

Despite our coworkers’ lack of experience in working with diagrams, they jumped in and came up with very illuminating work.

What we learned this time

There’s a lot going on in these diagrams, and not all of them strictly fit within the confines of the draft diagram we provided for the groups to work off of. However, it’s our opinion that many of these deviations from the original diagram uncover insightful looks into the way our coworkers think about archival data and where they expect to find linkages and relationships.

When asked about the motivations behind making the blank node, the answer was often extremely simple: it’s hard to find the entire corpus of Ford Foundation records in one spot. Secondly, we noticed a lot of groups trying to make relationships between different agents. We’re not positive about what our coworkers are trying to tell us, but the desire to show relationships between two different agents in regards to collections is interesting to us. Our inference is that our testers were looking for different ways to show connections outside of the traditional archival relationships. Ultimately, none of the groups had any major changes for us except to find a few flaws in our relationship linkages.

Finishing touches

Coming out of the final sessions, we had a definite model to work with, so the next step was to “finalize” our data model and share it out to the community. Finally, we got to a point where we were ready to share our work out.

We worked in Github because we wanted to make this work open to anyone that could use it, also, we wanted a way for others to comment and provide feedback on our work. We sent out a call for comments, and got about 10 really high-quality suggestions that ultimately shaped our final work.

What it’s all for

I’ve been talking about a lot of process, but I think the main takeaway is that when you work with others, you uncover new angles that you might have missed working alone. By valuing our coworkers’ prior labor and expertise, we can help them grow professionally and learn new skills while using those skills to help our work.

Data modeling is becoming a core concept for many in our field. It can be scary and intimidating to think about at first, but modeling is a skill that has to be learned, like any other, but it’s not one that’s so specialized that a processing archivist, reference archivist, or really anyone couldn’t it pick up. Ultimately, we had a stronger product, and our coworkers got hands on experience working with, and thinking about models, thus increasing the overall organizational data literacy.

Training Program - Bonnie Gordon

I primarily work with digital preservation and born digital, I’m going to talk about the training program we designed and implemented as part of the first phase of Project Electron.

As Hannah described, the first part of this project was to create an automated and scalable way to transfer digital records that would support standards compliant ingest, maintain compatibility with existing standards for data content and structure, and support established archival processes for accessioning and ingest. Since the implementation of the new system was to handle processes that are new for our appraisal and accessioning archivists, and the tools themselves would be new, we realized that these archivists, who are based in our Collections Management Team, may need additional skills and support to complete these tasks.

As Hannah also mentioned, prior to this project we had not implemented a holistic born digital program, so specific competencies for born digital accessioning were not defined. In thinking about what skills were needed going forward, we had to imagine what new tools and processes would be part of born digital appraisal and accessioning in the near future. While there were requirements developed for the tools we would be using, they were not yet created, let alone in place. And as I mentioned, the new tools would be standards-based, and adhere to archival principles–so a main focus would be on the theories and underlying skills so that our archivists would be equipped to make good decisions using the tools provided.

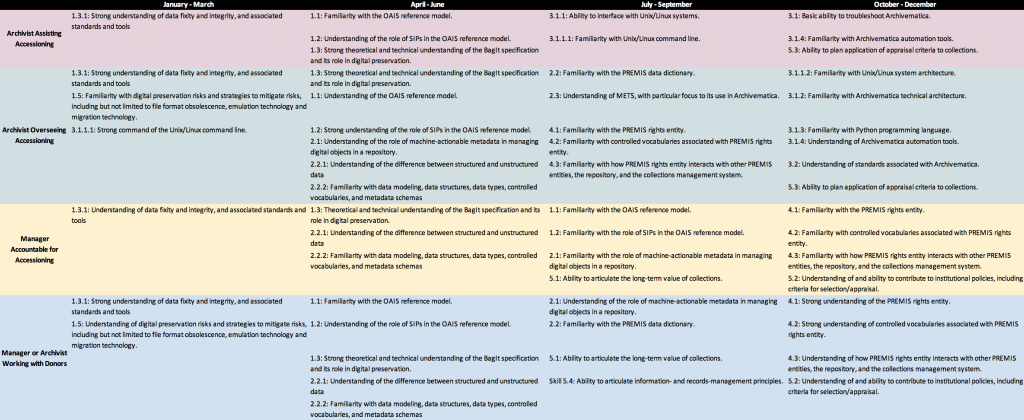

Skills

To get our archivists to this place, first I needed to come up with the specific skills that each role would need by the end of the year. I did this two ways: by using external frameworks, and by thinking about what tools and processes would look like and what skills would be necessary. For the former, the primary source that I used was the DigCurV Curriculum Framework, which was funded by the European Commission and developed to identify, evaluate, and plan training in digital preservation. In this framework, skills are divided into four domains: Knowledge and Intellectual Abilities, Personal Qualities, Professional Conduct, and Management and Quality Assurance; and there are three “lenses”: Practitioner, Manager, and Executive. For this project, I largely drew from the Knowledge and Intellectual Abilities domain, and the Practitioner and Manager lenses.

I then thought about what systems we currently use, that would be heavily implicated in the digital appraisal and accessioning modules of Project Electron. This included Archivematica. I used questions like “What does one need to know to troubleshoot Archivematica?” and “What standards is Archivematica based?” to come up with corresponding skills. I then thought about future systems, like our transfer application Aurora, and asked similar questions. For example, I knew that we would be using the BagIt standard for all transfers from our donors. But it was important to not only include “understands BagIt,” we wanted to make sure the underlying skills and competencies were spelled out.

After thinking through all skills and underlying skills, I grouped them together into four overarching skills:

- Digital preservation principles and the role of digital preservation tools, including the OAIS reference model, the BagIt specification, and an understanding of digital preservation risks and strategies to mitigate those risks

- Technical metadata and its role in managing digital objects in a repository, including the role of machine-actionable metadata, the PREMIS data dictionary, and METS

- Archivematica’s role in the digital preservation environment, including the ability to troubleshoot Archivematica, and understanding standards associated with Archivematica

- Machine-actionable rights statements, including the PREMIS rights entity and associated controlled vocabularies

Roles

In thinking about what skills would be needed, thinking about what different roles were involved in accessioning was key. This involved separating out the types of work–for example, appraisal and accessioning–and at what level the roles were engaging with the work–for example, practitioner vs. manager. It was important for us to have the roles not to be tied to specific people, and to go even further, we tried to not tie the roles to job titles. The roles would be more permanent than specific staff or even specific job titles; further, separating out roles would let us see if our current organizational structure reflected how work had evolved, and clarify who should be doing what. This also acknowledged that one person may have multiple roles. This required thinking about current roles of appraisal and accessioning, but also thinking about what roles would be part of work in the future.

I came up with four different roles

- Archivist or manager working with donors, who are staff and managers who interface with donors. I had initially broke these out into two different roles (managers and staff), but it became clear that the skills–at least as they relate to technical skills and digital preservation theory–were the same. The focus of this role was on a high-level understanding of digital preservation theory and standards so that they could effectively explain concepts to staff at our donor organizations.

- Manager accountable for accessioning, those who oversee the accessioning process and are responsible for accessioning policies. As with the previous role, the focus was on a high-level understanding of digital preservation theory and standards, so that they can effectively make policy decisions and supervise appraisal and accessioning work.

- Archivist overseeing accessioning, who are staff who are responsible for project managing accessioning. This role would require knowledge of digital preservation theory and standards so that they could make decisions on the ground. Additionally, this role would require knowledge of specific tools and systems, such as Archivematica.

- Archivist assisting accessioning, who are staff who perform specific tasks associated with accessioning. This role often works alongside the archivist overseeing accessioning. It was important for folks in this role to understand the theory behind the specific tasks assigned to them, as well as develop the technical skills required for those tasks.

Resources

The next questions we needed to ask were how and where our could staff get this training, and what resources were required to make that training happen. This meant evaluating for each skill what workshops, webinars, articles, and other things were out there. When looking at training resources, we asked Was it at the appropriate level? Would it fit into our timeline? Does it require travel? Several non-salaried staff–that is staff, who were unable to travel, were targets of this training. In addition to looking at webinars and online courses through professional organizations like SAA, we evaluated whether sites like Lynda.com and Codecademy had relevant courses (which in a few cases they did). We also looked at what relevant readings were available, whether blog posts, articles, or books. After seeing what was out there, we figured out what needed to be done internally, what the amount of resources would be require. This included everything from support for the aforementioned resources–like a facilitated discussion on readings or a debrief after a workshop–to building trainings for certain topics from scratch.

Timeline/Implementation

After understanding the skills, roles, and resources required, the next step was to create a timeline. We broke the calendar year into quarters, as that was easiest to manage. In order to begin figuring out a timeline, we thought about what skills built upon each other, and put the underlying skills first. We then balanced out the timeline using three factors: making sure each role had a somewhat even distribution of skills to learn each quarter (with the understanding that some skills were larger than others), thinking about what skills required internal support and when that internal support would be available, and where skills overlapped for several roles, making the timeline line up there.

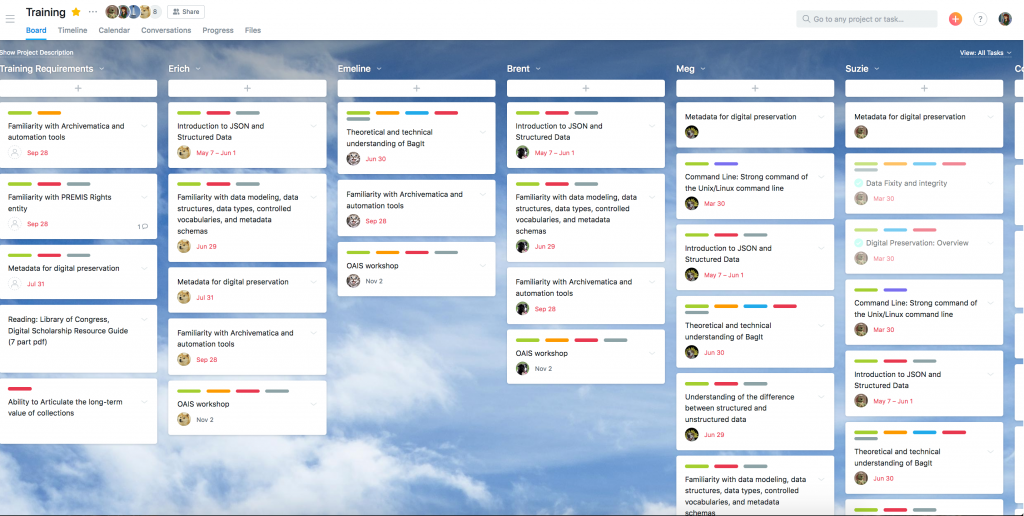

After this timeline was approved by senior leadership and the Head of Collections Management, we turned it into an Asana project–Asana is the project management tool that we use as an organization. We used the “board” type of Asana project, where the first column was an “training requirements” column, followed by columns for each member of the Collections Management team, followed by a “completed” column. The “training requirements” column was where I could add each task and attach potential resources, and then the Head of Collections Management could assign the tasks to the relevant staff (including herself). Deadlines were assigned to tasks that either corresponded with each quarter mentioned above, or if there was a workshop or webinar, the date it would be held. When staff completed readings or attended trainings, they checked the associated tasks off.

Conclusion

I mentioned earlier that these skills needed to be attained by the end of the year. So now that we’re almost there, how has this gone? Of course, as with any project, there were complications for our tight deadlines. This included two folks from our Collections Management Team leaving in February, and two other folks going on parental leave this year. In the former case, one of the advantages of having this plan was having already thought through competencies we would want in job candidates, and what skills we could realistically expect to train them on once they started. And in both cases, one of the impacts was that staff had to manage this training with an already increased workload. While this was not ideal, I think creating a concrete timeline and doing the legwork of finding resources (while giving options so that staff had some choice), made this more manageable. And the folks doing the training felt the same way: I checked in with everyone in July, and staff generally felt confident about the skills they had learned and how everything was going.

Concluding remarks

The title of our talk claims that this work has helped us enable cultural and organizational change, and I think all our work on Project Electron has successfully helped us grow as an organization. While many of these projects saw the three of us in the guiding or leadership roles, we’ve also been learning as we go. Incorporating participatory UX activities into the development and testing of new technology involved the users and future maintainers of that technology in ways that can encourage transparency, incorporate perspectives from across the organization, break down common barriers to engaging with tech development, and consequently contribute to the long-term sustainability of digital infrastructure. It’s important to think critically about the skills staff need to do their work, and seriously provide the support and resources to enable them to achieve those skills and give them the space they need to learn. And finally, working and learning collaboratively on new tech projects with coworkers uncovers ways to strengthen the end product and grow our institution’s skills at the same time.

Throughout all of our work, we wanted to recognize and value the knowledge that our coworkers bring to the table, leverage that invisible expertise, and use the experience to not only create a stronger system, but to also give others the confidence to work with that system and a deeper understanding of how it works. On the D-Team we strive to help others feel comfortable working with technology, and our approach to Project Electron encapsulates that desire.

Thank you.