The service design-based research and analysis Hannah described in an earlier post revealed two fundamental challenges to rethinking our digitization processes: nobody understood the entire process from end-to-end, and the process was not observable. It was clear that until we were able to address these fundamental problems, we would essentially throwing darts while blindfolded and dizzy. We’d have no idea where to intervene or whether changes we’d implemented had resulted in things getting better.

As a result, we chose to start in a very specific way, by making the units of work that are part of this process (digitization transactions) smaller, and de-siloing the entire process so that archivists could process a transaction from start to finish. While this might seem a somewhat arbitrary place to start, these changes are based in ideas developed in the Toyota Production System (TPS), a predecessor of Lean Manufacturing methodologies in wide use today.

The Toyota Production System

Developed in the 1950s and 1960s through Toyota’s operational practices, TPS is concerned with the efficiency of manufacturing processes, but unlike other theories of industrial management like Taylorism, workers in these processes are not merely replaceable cogs from whom the maximal amount of labor must be extracted, but key partners whose expertise and experience are essential to its ultimate goals. By increasing both the autonomy and responsibility of individual workers, TPS argues that engaging everyone in the process of continuous improvement means that change can happen incrementally and with less friction.

The System is often described as being primarily a method of reducing waste, which it argues is produced by “overburdening” – or imbalance – in processes. To achieve this aim, it puts forward two concepts: making only what is needed, when it is needed, in the amount that is needed (also known as just-in-time); and automating with humans in mind. As a result, it advocates for the reduction of in-progress work and inventory and ensuring that work is leveled out across an entire process, so individuals or machines aren’t overwhelmed.

Implementing these ideas is a lot like lowering the level of water in a river. The river flows faster, but it can also reveal all the rocks that were lurking below the surface. Although they’ve been there all along, suddenly having them pop up can feel incredibly unnerving and cause a fair amount of chaos. However, seeing the rocks is the first step to both consistently navigating around them or, better yet, removing them entirely. Visibility is also key to building a shared culture of continuous improvement; a shared understanding of the existing landscape is a prerequisite to solving its challenges.

Many of the ideas that are part of TPS have found their way into non-manufacturing industries (for example, DevOps draws substantially from the System, read The Phoenix Project if you don’t believe me), but it’s important to note that the TPS is not some sort of magic bullet that can fix all process problems. It works best when processes have some resemblance to the inputs, outputs, and constraints of a manufacturing process. It’s also not great at dealing with disasters or sudden unexpected spikes in demand, as evidenced by all the supply chain problems that arose in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic.

What We Did

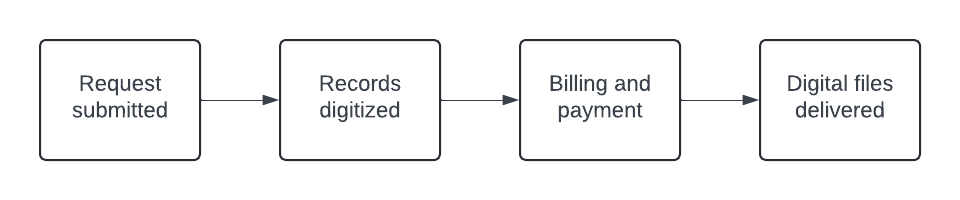

As we analyzed our onsite digitization process, we quickly realized that it strongly resembled a manufacturing process. Digital surrogates are created from analog documents or photographs based on requests from researchers, who are then billed for each transaction. Once payment is received, the digitized content is delivered. In other words, it is a linear process with predictable inputs and outputs.

Additionally, we knew that our colleagues on the Access team responsible for digitization have a broad range of skills, experience, and length of service at the RAC. They also have additional work responsibilities outside of digitization, so the process had to be simple enough to be easily remembered and efficient enough that it could be completed in under an hour.

Smaller Units of Work

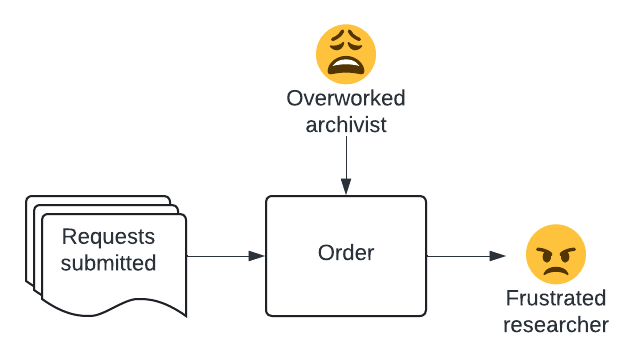

As I mentioned earlier, one of the big things we did was shrinking the units of work, which in this case meant making requests for digitized records (which we call “transactions” in our backend system) smaller and more predictable. DIMES, our discovery system, has a feature which allows users to save items in their list, and then submit requests based on those saved items. In the past, when a user would request digitization of multiple items from DIMES, we would group all of those together in one “order”, which would then be processed as a unit. Unsurprisingly, these orders could be quite large, and tended to act as large boulders in the stream, blocking the flow of other smaller orders.

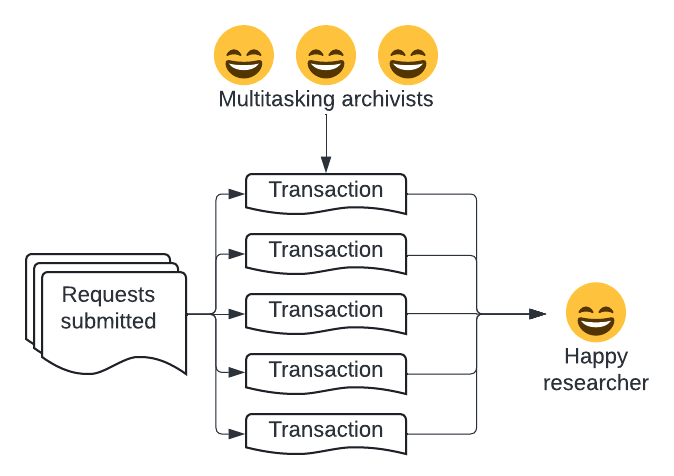

To address this, we made a number of changes to our requesting systems and did away with grouping individual requests into orders. Now, each item that is requested comes into our systems as a transaction which can be processed individually. This means that digitized records will start to flow to researchers as soon as possible, rather than being delivered in one large dump when everything has been digitized. The uniformly small size of the transactions also gives our colleagues who are digitizing records confidence that they can pick up a transaction and digitize it relatively quickly, so they don’t need to block out their entire day to do digitization but can fit it in more easily amid other responsibilities.

Another important part of this was controlling the flow of requests into the system. We implemented an annual transaction limit, which requires researchers to be selective about what digitized records they request. This eliminates the huge spikes in demand we might see otherwise, resulting in a more predictable flow.

Autonomy and Responsibility

Another major change we made was removing specialized roles from the digitization process, particularly related to billing and delivery, and empowered archivists to see digitization transactions all the way through the process. This reduces the need for handoffs (which require additional communication mechanisms), or time spent waiting between steps. This gives our colleagues doing the work a much clearer sense of accomplishment and also allows us to scale the process up or down more easily.

We also developed simple and visually appealing documentation for the entire process, so that archivists can easily remind themselves of what to do when necessary.

Observability

To support a more holistic approach to onsite digitization, we implemented very simple task tracking through which digitization requests can be claimed, moved to an “in process” status, and then completed when the files have been delivered to the researcher. This helps us see how our capacity is tracking against demand, and also allows us to confidently message out to remote researchers about anticipated wait times. Over time, having better visibility of the entire process will help us know where we can most effectively intervene to improve the process, rather than using guesswork.

Future Work

It’s early days, but we’re already starting to see our digitization backlog decreasing slowly but steadily. As we get more familiar with the process, I expect we’ll see that backlog disappear entirely.

We also have some other ideas of future work. One of the major concepts of the Toyota Production System is automating with humans in mind. We hope to introduce some automation to reduce time spent generating PDF derivatives, and also to support long-term access to the digitized records via DIMES. We’ll write more about that piece of the work when we get there!