As we’ve continued to refine Aurora’s functionality, and improve the application’s usability and accessibility, we’ve also been building out microservices applications which integrate a number of systems, moving digital records and data between them. Systems integrations work is not new to us at the RAC, but the integrations we are building for Project Electron are extremely mission critical. Because of that, they need to be reliable, scalable, holistically managed, modular, visible to and owned by staff at all levels of expertise. We also want them to automate routine and repetitive tasks, while supporting the value and dignity of archival labor by keeping human judgement and principled decision-making in the loop.

What’s a microservice?

Although there are many definitions of what a microservice is, for our purposes we define it as a piece of code that performs a clearly defined and independent function: it does one thing and does it well. Microservices are usually part of an event-driven infrastructure, which means that they are triggered on an as-needed basis by other services or systems.

Another way of thinking about microservices is that they are the seams that stitch systems together and turn single pieces of functionality into the fabric of a platform. These connections are not one-size-fits-all. Just as a tailor might choose different kinds of seams and stitches based on what kind of bond they want - strong, decorative, flexible, permanent or temporary - as well as the characteristics of the materials they want to join - what kind of edge does it have, do materials overlap or butt up against each other - microservices can be written in many different languages and interact with systems and each other using a variety of protocols. We’ve chosen to develop our microservices using a common set of languages, frameworks, and libraries, but that doesn’t preclude us from using different languages in the future, or even reimplementing existing services in a different way.

Why we chose this strategy

As Hannah wrote in an earlier post, we think the approach we’ve chosen gives us the best shot at achieving these goals by providing a single interface in which we can manage integrations, log activity, and manually recover from failures. We’ve given ourselves the ability to add or remove integrations iteratively, mitigate disaster when it strikes, and support the growth of our colleagues as well as our organization.

A microservices approach also allows us to work consciously and intentionally in the spaces between systems. Most of the systems we use to do our work - ArchivesSpace, Archivematica and Fedora - are community-driven open source solutions. This means that, although we participate in the communities which develop and maintain these applications, we don’t have total control over their functionality either now or in the future. Choosing to build integrations outside of these systems means we don’t have to spend as much effort keeping those customizations up to date. It also means that we can incorporate functionality which is particular to our needs without foisting our specific edge cases on everyone else.

However, owning these integrations as an organization will require us to develop and maintain an understanding across the RAC of what these systems do, how they work together, and how that functionality intersects with archival processes. I’d argue that’s a good thing, and that developing this shared understanding will lead to more durable, documented and well-maintained applications, and a more technically-competent organization.

Stitching the layers together

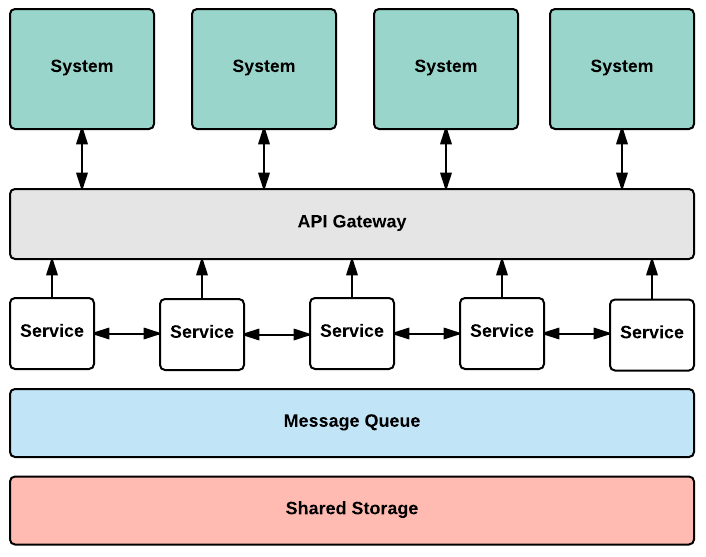

One way to think about our microservices environment is as five distinct layers tied together in different ways.

Sitting at the top are systems, both those we use now as well as ones we might use in the future. Because they are located their own layer, we can swap systems in or out, and adjust how we interact with them as necessary.

Below the systems layer is the API Gateway. This layer handles request redirection, logging, and the overall administration and management of services. All requests to and from systems pass through this layer, which means that we can limit which service endpoints are publicly exposed, and which are only available within the microservice layer. The API Gateway allows us to configure how systems are connected, which means we can easily add or remove a service should the need arise.

After requests have passed through the API Gateway, they enter the microservices. These services interact with each other in two ways: they either trigger another request by sending an HTTP POST request along with a payload, or they queue a request for the next service in the chain.

Supporting the microservice layer is a message queue, which can be thought of as a simple postal system, where messages which trigger services are delivered to that service’s “inbox” via a request from another service. Using a messaging layer gives us better overall information about what’s happening in the microservice layer and, because these messages are asynchronous, helps us scale and trigger other tasks without waiting for requests to complete.

Last, a shared storage layer supports the services by making transfer files accessible to each service. This allows us to move files between services without using a network transfer protocol like SSH or rsync, improving performance and reducing complexity.

Introducing our microservice applications

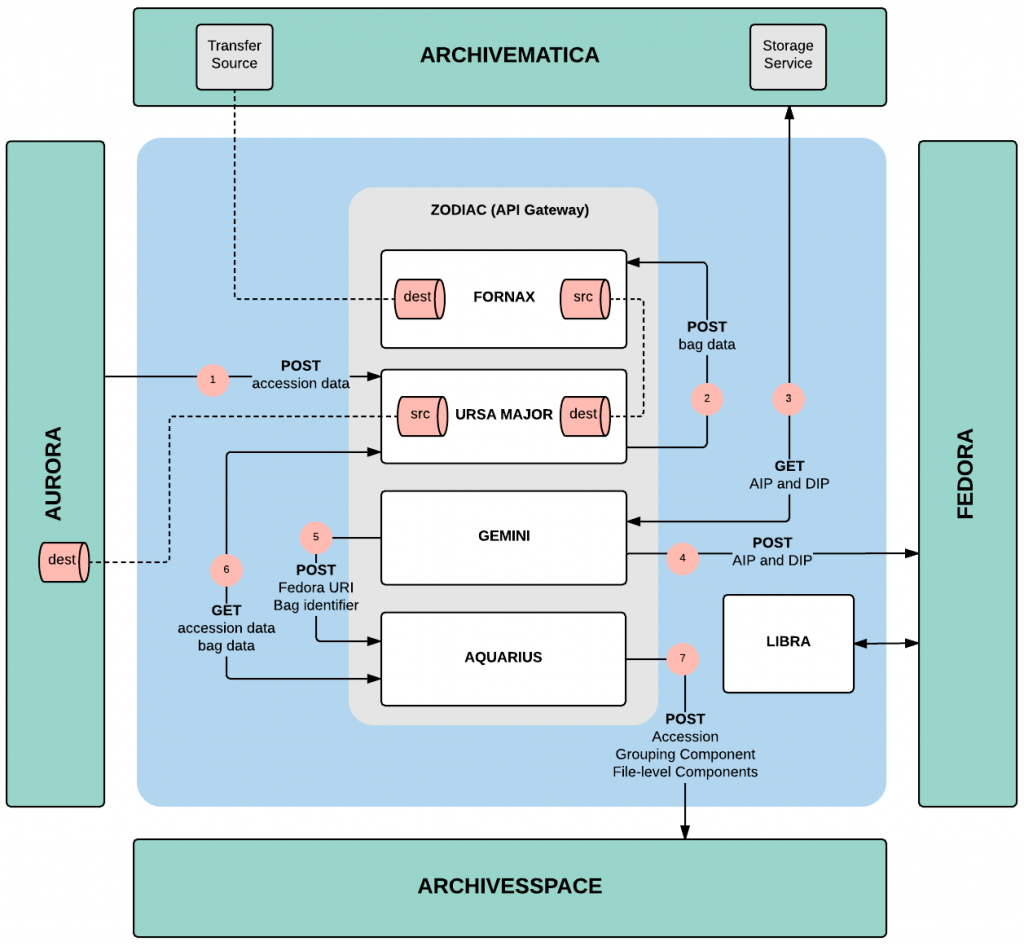

The diagram below represents another way to think about our system architecture. Here you can see how the microservice applications help sew together Aurora, Archivematica, Fedora and ArchivesSpace using HTTP requests and shared storage directories, and how data flows between these applications in a roughly clockwise direction, starting with Aurora.

To make deployment easier, and to reduce redundant code, we’ve clustered our services together into five applications, each of which comes with a Docker container, a fairly comprehensive README, and a constellation-themed name. As with all Project Electron products, code is open source and released under an MIT License.

Zodiac

The first is our API Gateway application, which serves as a management and logging wrapper for the services layer. It allows us to add, configure and track activity within each service, as well as in the system as a whole. This means that we can easily redirect services, and turn them on or off with the click of a button. We can also manually trigger services when we’d like to retry a request or debug something that’s gone wrong.

If you’re interested in checking out this microservice layer as a whole, I’d suggest starting with Zodiac’s GitHub repository, since all the other microservice applications are included as submodules, and there’s also a docker-compose file which allows you to stand up all of the microservice applications at once.

Ursa Major

When accessions are created in Aurora, that data is delivered to Ursa Major. The accession data is stored there along with data and files for each of the transfers in the accession. Other applications can then access this data store without making requests against Aurora’s API, which increases the overall scalability of the microservices layer and also reduces authentication complexity.

Fornax

After being stored in Ursa Major, transfers and their associated data are handed off to Fornax, which creates Archivematica-compliant transfers and then starts moving those transfers through an Archivematica pipeline. Through the use of a processing configuration file, we hope to limit the need for archivists to interact with the Archivematica Dashboard UI to occasions when troubleshooting is required.

Gemini

Once transfers have been processed through the Archivematica pipeline, Gemini downloads the packages and stores the resulting files in Fedora (our code leans heavily on Graham Hukill’s pyfc4 Python library). We add very minimal metadata to these packages in Fedora, preferring instead to use ArchivesSpace as our canonical metadata source.

Aquarius

When Gemini has finished storing files in Fedora, it passes information about each package (including where it is stored in Fedora) along to Aquarius. Aquarius reaches back to Ursa Major to get additional data about each package, transforms that data, and then creates an accession (matching the accession in Aurora), a record group component in a resource record (representing the same level of aggregation as the accession record) and, within that record group component, file-level components for each transfer in the accession. Aquarius is easily the most complex microservice application we’ve developed, given all of the data transformations and interactions with ArchivesSpace (for which we rely heavily on ArchivesSnake).

Over the coming months we’ll be deploying these systems, and no doubt making other tweaks along the way. Stay tuned for more updates as we continue to stitch things together!