This post in our series on reimagining digitization processes is all about digital surrogate file naming and organization, which warrants its own post because a lot of other processes hinge on developing a digital surrogate file management approach that is standardized and actionable to allow both humans and machines to do things with those files.

As I noted in my post on researching and analyzing our existing digitization processes, our previous file naming approach for onsite digitization work necessitated time-intensive and error-prone labor that was not facilitating long-term preservation and access, and made it difficult to DO things with the digital surrogates we created other than immediately deliver them to the researcher who requested them. We could not reliably or quickly know if something had already been digitized, and we were struggling to get digitized files into our pipeline to assign PREMIS rights statements,make them available on DIMES via IIIF or manage and preserve them reliably if they could not be made immediately available online. I’ll restate something a wrote in my previous post in this series because I think everyone working in archives and beyond can benefit from this idea: we can find ways to forgive archival debt and ourselves for getting into some well-intentioned messes, re-ground our work in our mission and values, and keep trying to improve how we do our work in a way that benefits the people doing it and the people who use archives.

Use unique machine-actionable identifiers

Some years ago, we made the decision as an organization to scan the entire archival object when a researcher requests something. Even if that researcher may only need a few pages, we determined that scanning the entire object better supported physical preservation concerns, the provision of long-term access, and the ability to leverage existing archival description to manage the digital surrogates.

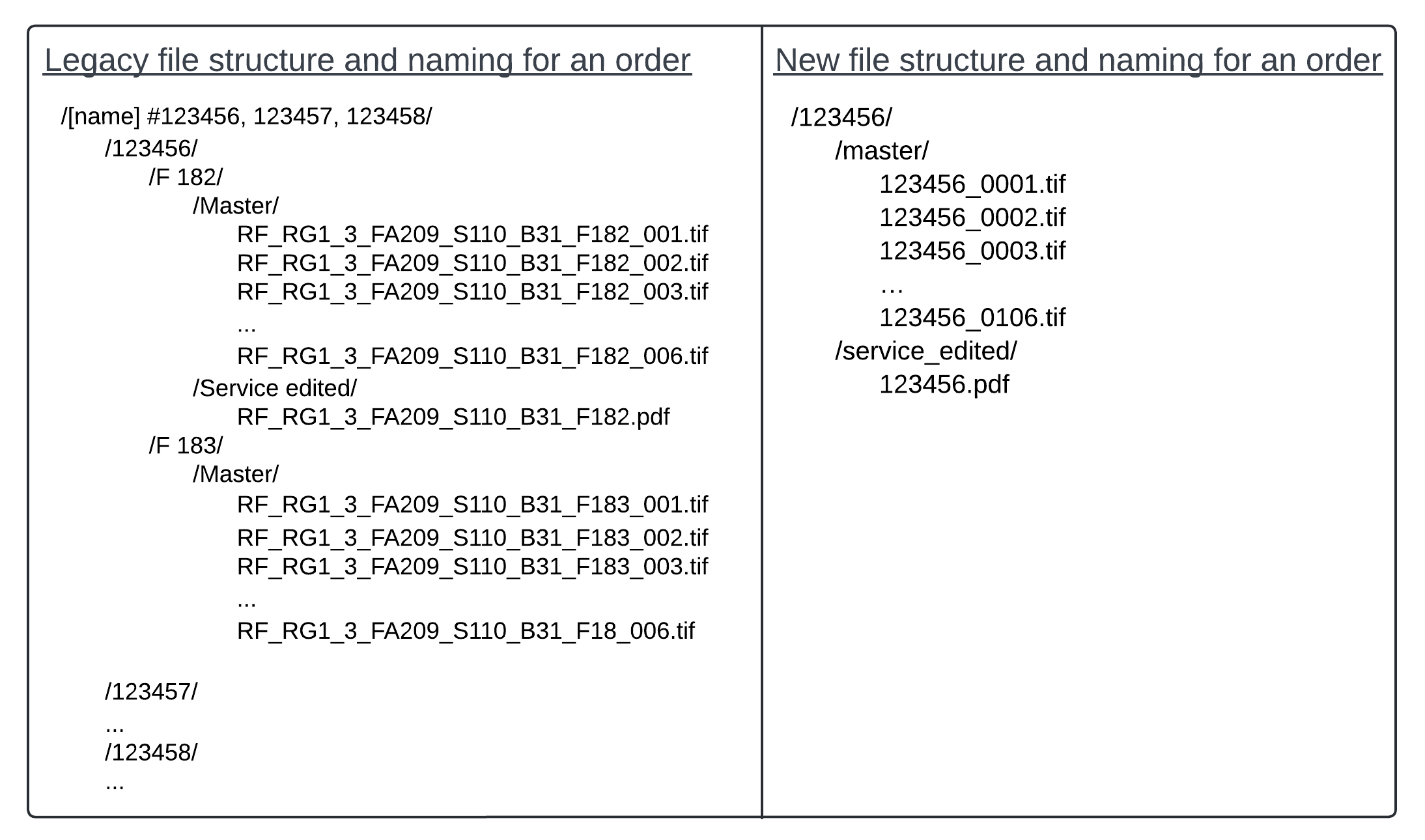

Our legacy digital folder/filenaming approach used a common technique, which is to organize and name things so that a human can look at the thing and know something about what it is without external systems. To this end, we nested folders within folders to organize multiple transactions for one researcher request, separated physical archival folders into corresponding digital folders with that scanned material, and named the file using archival description context abbreviations, which looked something like: RF_RG1_3_FA209_S110_B31_F182_001.tif

The two changes we’ve made to better manage and provide access to digitized content are:

Break our digitization workflow into smaller units of work, as Hillel detailed in his recent post. Now one digitization request “transaction” from a researcher corresponds to one “archival object” as designated in our archival description.

Name the digital surrogate files using the request transaction identifier.

We let go of the idea that we need to try to communicate metadata in a file structure or filename, and with those smaller units of work where there is a one-to-one correspondence of transaction number to archival object, there is no need for managing multiple transactions in a single request. The filename is now a unique identifier that exists in our request management system (we currently use Aeon), and that request management system includes the corresponding identifier for our archival description system (the ArchivesSpace refid). For each request transaction we now use a simple file structure (see Figure 1).

While we are actively managing a researcher request, we can easily access the request information in our system using the request transaction identifier that is also the filename. If we need to know something about the archival metadata, we can use the ArchivesSpace refid to access that object in ArchivesSpace.

What machines can do with a unique identifier

The power of naming folders/files with identifiers and standardizing structure is not just that it simplifies and reduces the repetitious manual actions of creating and naming folders, it also allows us to automate actions and move data between systems:

-

Support project management. Hillel wrote a script that watches an Aeon queue, and when a transaction is moved to that queue, a new task named with the transaction identifier is created in our project management system (we us Asana). So now we can track new digitization requests and assign them to people in our project management system.

-

Rename files. The data in the request management system is deleted periodically to follow our records retention schedule/respect researcher privacy, and we want to be able to link the file to its archival description in ArchivesSpace. So once the researcher transaction is complete and the requested file is delivered, we can automate renaming files to their corresponding ArchivesSpace refid. This is something we did manually in the past.

-

Assign rights, package and preserve, and make content available online. We use PREMIS rights statements, which we define and make available via an API to assign rights to archival objects. We then package the digitized content into bags, manage TIFF files for long-term preservation, and make the PDF access files available online if the rights allow. All these processes are automated, and none of them can happen without a standard file structure with master TIFF files in a “master” folder, the PDF in a “service_edited” folder, and files named using the ArchivesSpace refid.

-

Build other systems to manage digital surrogates. We currently save digital surrogate files on a local server until files are ingested into our pipelines for preservation and to provide online access. However, some objects cannot be made available online, but we still need to be able to easily know about and access those files as archivists. We don’t have a solution yet, but having a standardized and machine-actionable structure makes architecting new systems and/or tools possible now that we have the ability to automate actions and fetch additional data from associated systems like Aeon and ArchivesSpace.

Hillel will be publishing the next post in the series on how we are managing digital surrogate files that we get back from offsite vendor digitization, and you’ll see that there is an alignment of approach whether the digitization is done by Rockefeller Archive Center staff or not: using a standard folder structure and machine-actionable identifiers allows us to automate what computers can do while respecting the time and energy of humans to do what we do.